Between the years 1942–1945, three different staged films were created in the Theresienstadt (Terezín) Ghetto. Only a few short shots or fragments of the original versions have been preserved.[1] The most famous of these became the propaganda film Theresienstadt. Ein Dokumentarfilm aus dem jüdischen Siedlungsgebiet,[2] which became known as Der Führer schenkt den Juden eine Stadt – The Führer Gives a City to the Jews; Kurt Gerron was involved in the making of it. Employees of the Prague Aktuality office worked on the film at the end of the summer of 1944; they handed it over to the Nazis in the last weeks of the war in March 1945.

In the 1970s, Karel Margry discovered three rolls of a 16mm film in Poland that contained shots from the first Theresienstadt film shooting in the fall of 1942. It isn’t clear why cameraman SD Hauptsturmführer Olaf Sigismund shot this „film about a film“. But it reveals some very interesting information about the work on the lost film. When the exterior scenes at the building site of the Bohušovice railroad were shot, Sigismund’s camera captured, among other things, the figure of a smiling young girl with a scarf.[3]

A young Dutch historian thought at the time that the woman in the shot was “the Jewish female director of the 1942 film: Irena Dodalova.”[4] Years later, when biographical information about this Czech pre-war filmmaker,[5] who founded the first animated studio in Prague in the 1930s, IRE film, was published, it was immediately apparent that the girlish face in the scene couldn’t have belonged to a more than 40-year-old woman.

For decades the question remained: who was the smiling girl that Sigismund’s camera captured?

A viewer in Australia uncovered the answer. He saw the smiling girl on YouTube in an edited film about Himmler[6] and recognized her as his relative Lotte[7]. One of Lotte’s daughters, Mrs. Vivien Lipshut, sent an e-mail to the Czech author of a book on Irena Dodalová, requesting to correct K. Margry’s credit on YouTube, because it was her mother, Lotta Brinitzerová-Porgesová, who was the smiling girl in the scarf in that scene.

And so the story of the Theresienstadt film deepened.

Lotte Brinitzerová was the granddaughter of the important Prague businessman August Lindt.[8]

She was born in Frankfurt on December 20th 1922, but spent her youth in Prague, where her mother returned after divorcing her first husband. In the 1930s, she studied at a German school, but she was bilingual and her Czech was excellent. She was interested in art and young artists from various disciplines were part of her circle of friends. During this time, David Friedmann painted her portrait and she modeled for the photographer Karel Ludwig.

In December 1941 she was transported with her family to Theresienstadt. She described what she experienced in this period of the Jewish holocaust in an interview for the USC Shoah Foundation.[9] In it, she mentioned making a film in Theresienstadt, where Lotte was part of the Jewish film crew as a make-up artist to the „actors“, more precisely to the Jews who were filmed. (For more about how the film was made and how makeup was ordered from the Third Reich from the Schmink company, see JUDr. Hanuš Král[10]). In December 1943, she was transported to Auschwitz, and from there to a concentration camp in Hamburg. She was liberated together with her sick mother in Bergen Belsen.

Lotte Porges contributed several photographs to the interview, which helped fill in certain gaps from her life.

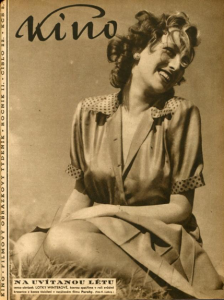

The enclosed copy of the front page of the journal Kino[11], where she was introduced as “Lotka Winterová“ (the last name of her mother’s second husband) shows that the charming girl performed in Radok’s costume film Parohy (1947). She had apparently been thinking about a career as actress at the time, as attested by the many more photographs of her saved by her family in Australia. (Unfortunately, there is no list of films she appeared in; she started out as an extra, and existing Czech film sources don’t register the names of people who worked as extras.)

The name of the photographer who took the picture on the cover page of Kino, Karel Ludwig, brought us to Blanka Chocholová, who looks after his archive. Blanka Chocholová remembers Lotka Brinitzerová-Winterová, because she belonged to Zdeněk Tmej and Karel Ludwig‘s[12] circle of friends before she was removed to Theresienstadt. Her portraits from the time are stored in the archives of the photographers.[13]

According to Blanka Chocholová’s recollections, Lotte met the photographers Ludwig and Tmej again after liberation in the Bergen Belsen camp, when the young photographers traveled through the post-war former lands of the Third Reich together with Miloš Makovec and Erich Kaizr.[14] But the joy from their meeting didn’t last long, for the young men encountered a serious problem – their film equipment, including exposed film, disappeared from their car. The British camp administrators wanted to help the Czechoslovaks, and so they recommended that the young men visit the synthetic silk factory nearby, where they could select the necessary photographic equipment. Lotte accompanied them to the factory, and that’s probably when the photograph with the microscope that Lotte Porges contributed to the USC Shoah Foundation website was taken.[15]

In 1947, Lotte Brinitzer married Pavel Porges. Together with her husband and her first daughter Daniella, she emigrated from Prague through Paris to Australia. Here, Lotte raised two daughters and devoted herself to her art, in particular to design. She died in Melbourne in 2010.

The author would like to thank Blanka Chocholová for sharing her memories of Lotte and her consent to use Zdeněk Tmej‘s Lotte with the Microscope. Karel Ludwig/ Archiv B&M Chochola.

She would also like to thank Vivien Lipshut for her help with this topic and for sending photographs of her mother Lotte Brinitzer-Porges’s work.

The author would like to express special gratitude to the National Film Archive in Prague (Národní filmový archiv v Praze) for their consent to use photographs of Irena Dodalová and MUDr. Gertruda Klepetářová (Výstřihy 1942) and particularly to Miloš Fikejz (National Film Archive in Prague) for the scan of the cover page of Kino.

Notes

[1] Historians may have formed an idea about the content and appearance of the film solely by comparing shots that were secretly carried out of cutting rooms or based on fragments found in various archives and survivors’ memoirs. See also https://portal.ehri-project.eu/guides/terezin/film_fragments.

[2] Terezín. Dokumentární film z židovského sídelního území; Terezín. A Documentary Film from a Jewish Settlement Area. The film was only shown at in-house screenings in Prague and in the Ghetto (April 6th and 16th, 1945). Two longer fragments from the film have been preserved.

[3] O. Sigismund’s amateur film is archived in Poland under the name Obóz koncentracyjny w Teresinie (Filmoteka Narodowa), and in Germany under the name Theresienstadt 1942. Dreharbeiten (Bundesarchiv).

[4] Karel Margry, Utrecht, The first Theresienstadt Film (1942), Historical Journal of film, Radio and Television, Vol. 19, No. 3, 1999, p. 319.

[5] Eva Strusková. Dodalovi. Průkopníci českého animovaného filmu, see also The Dodals, Pioneers of Czech Animated film, NFA 2013.

[6] History Channel: Hitler’s Henchmen – Heinrich Himmler: The Excutioner. YouTube > https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=k3fLixLMGXE&sns=em

[7] Lotte Brinitzer, Winter, Porges (1922–2010).

[8] For more on the family, see the family memoir by one of August Lindt’s grandsons Jiří Kosta: Nie aufgegeben. Ein Leben zwischen Bangen und Hoffen. Bodenheim 2001, in Czech: Život mezi úzkostí a nadějí, Paseka 2002.

[9] Lotte Brinitzer-Porges, interview Code 18722, Aug. 20., 1996

[10] Hanuš Král, after 1970. Holocaust, tape 80. Jewish Museum Prague.

[11] Kino, no. 22, 30. 5. 1947.

[12] Zdeněk Tmej (1920–2004), Karel Ludwig (1919–1977), the classics of the Czech modern photography.

[13] http://www.vaclavchochola.cz/archive.htm

[14] Miloš Makovec (1919–2000), film and tv scriptwriter, director. Erich Kaizr (1919–1980), painter, illustrator, typographer.

[15] The photograph is thematically very similar to a shot from the film made in Theresienstadt in 1942. MUDr. Gertruda Klepetářová-Adlerová later died in Auschwitz.

Judith Haran

Great research! I’ve always been fascinated by what little I’ve heard of this film.

It feels like a discussion of this topic would be incomplete without at least a small reference to the section of Sebald’s novel, Austerlitz, in which A. discusses his search for a fleeting glimpse of his mother in the 1944 film. In the novel it’s a 14 minute fragment which he manages to slow down to 1/4 speed, with eerie effects. The passage is on pages 232-252 and is worth a read (as is the entire book, for those who haven’t discovered it yet). The blogger Terry Pitts also has a post on Sebald and H.G. Adler, a survivor who wrote both a massive history of the camp as well a novel, The Journey, about an unnamed society resembling Nazi Germany. Pitts’ blog post can be found at https://sebald.wordpress.com/2008/11/18/adler-theresienstadt-sebald/

A long, detailed, fascinating article about Terezin and Sebald can be found in German Life & Letters, vol 65, issue 3, for those with access to it: by Martin Modlinger, 11-6-2012, entitled ‘Mein Wahrer Arbeitsplatz’:The Role of Theresienstadt in W. G. Sebald’s AUSTERLITZ. According to a footnote, the novel was based on a true story.

Elmas Keller

Hello,

I am researching for a screenplay the story of Lotte Porges,

I would like to get in contact to Eva Strusková to get first hand information.

Can you help me with her email adres?

If you need more information about me,

please just write me.

Best Wishes

Elmas Keller

Viv

Hello,

I know Eva Strusková. Could you please get in touch with me. Thank you

Eva Strusková

If you wish to contact me, please, send me a message on the address

struskova@email.cz.

Peter Lipshut

May I ask what is your reason for researching a screenplay on Lotte Porges? What aspects of her life are you focusing on?

I may be able to assist.

Thanks

Eva Strusková

I am sorry, but I haven´t any plan to take a part for researching a screenplay on Lotte Porges.

Best regards

Eva Strusková

Petr Brod

To whom it may concern:

Lotte Porges, formerly Winter, nee Brinitzer is prominently mentioned in Frances Epstein’s memoir (Franci Rabinek Epstein, Franci’s War. A True Story, 2020), edited by Helen Epstein.

Her fate and memory is also at the centre of an ongoing court case in Germany (see https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/oct/08/survivors-daughter-sues-historian-claim-lesbian-liaison-nazi-guard and https://www.spiegel.de/geschichte/lesbische-beziehungen-im-kz-zu-intim-fuer-die-forschung-a-74df1056-ec60-44f9-a2b4-5697493d7a3f)

Best regards

Peter Brod

Prague