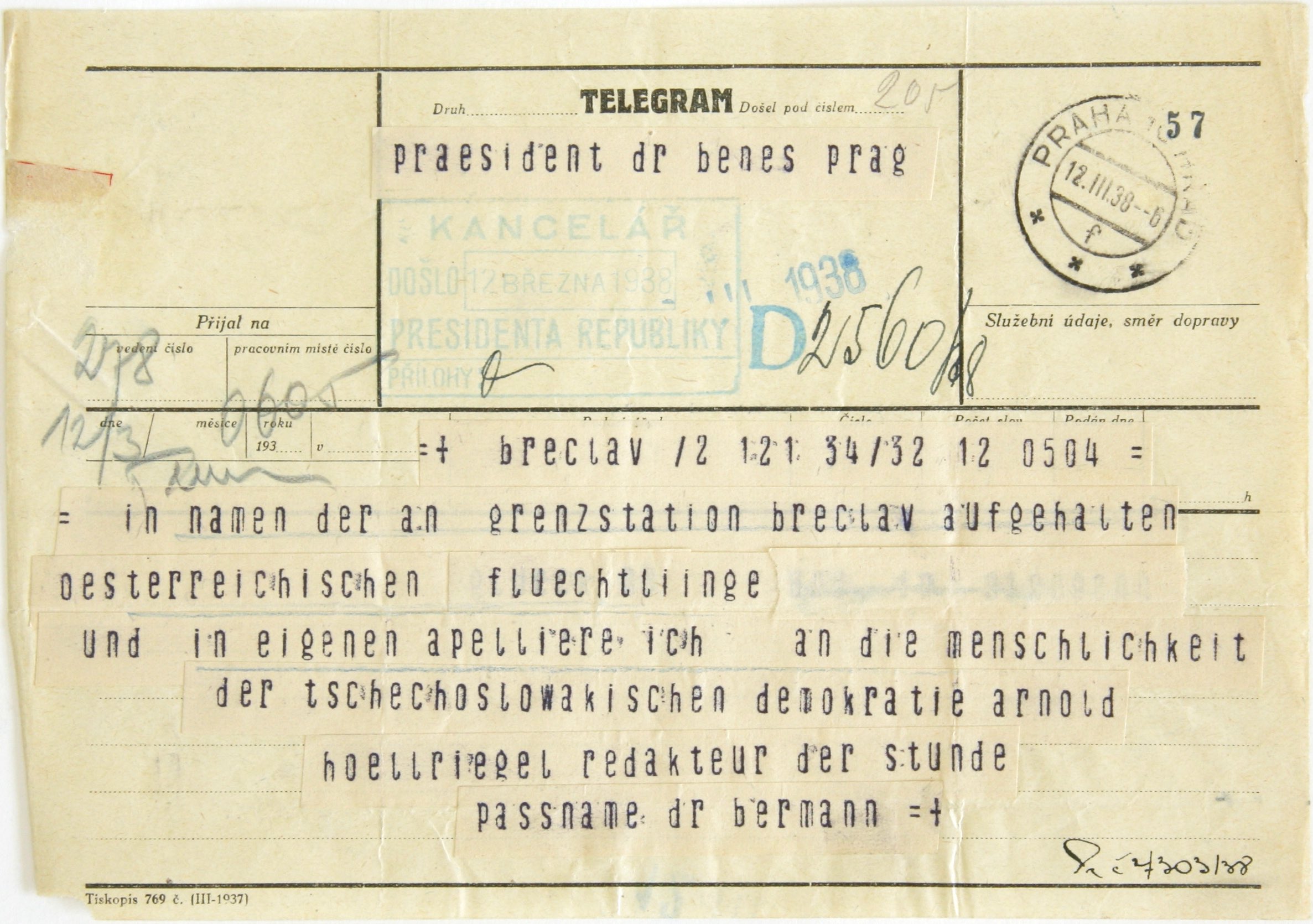

The journalist Richard Bermann was one of the many Austrians threatened by the Nazi regime who tried in vain to flee on the night train to Czechoslovakia the night of the 11th March 1938. After approximately 180 Austrian refugees were turned back at the border, Bermann appealed via telegram to the Czechoslovakian president for the refugees to be allowed entry:

The telegram, which can be found in the National Archives in Prague, documents not only the beginning of a wave of people fleeing into what would become one of the most important countries of exile after the Anschluss, but also the rapid closing of the border to Czechoslovakia for Jewish refugees.

The flight and expulsion of thousands of people across the Austrian-Czechoslovakian border and the increasingly restrictive Czechoslovakian policy towards refugees is an important – but also somewhat neglected – chapter in the history of Austria and Czechoslovakia and the Shoah. An online edition supported by the EHRI infrastructure and funded by the Future Fund of the Republic of Austria (Zukunftsfonds der Republik Österreich) for the first time brings together archival materials from Austria and Czechoslovakia, and documents from other countries, allowing for research on Austrian refugees to Czechoslovakia in the crisis year 1938.

The online edition Begrenzte Flucht – Austrian refugees on the border to Czechoslovakia in the crisis year 1938 contains official reports, correspondence and diplomatic notes as well as documents from Jewish aid organisations. Selected newspaper reports also show the reaction of the public – including the exaggerated emphasis on the perceived danger and the antisemitic overtones in the press. The edition gives special attention to documents that also attest to personal experiences of those fleeing and the escape routes they used. The editors chose to include rare interview reports compiled by the Czechoslovakian border authorities with Austrian refugees.

The Czechoslovakian Refugee Policy prior to the Anschluss

The online edition includes documents about the Czechoslovakian policy towards refugees prior to the Anschluss. Czechoslovakia began with a generally tolerant attitude towards refugees from Nazi Germany – and also political refugees from Austria after 1934. The state reacted in the same way as many other European states at the time: refugees were able to cross the border with relative ease in the first few years, but the real difficulty proved to be long-term perspectives for the refugees in exile. From the mid-1930s, the liberal policies and temporary acceptance was gradually rolled back and eventually abolished. The 1935 Czechoslovakian law regarding the residence of foreigners made the situation more difficult for refugees who would now be forced to regularly reapply for permission to remain.1

The Anschluss

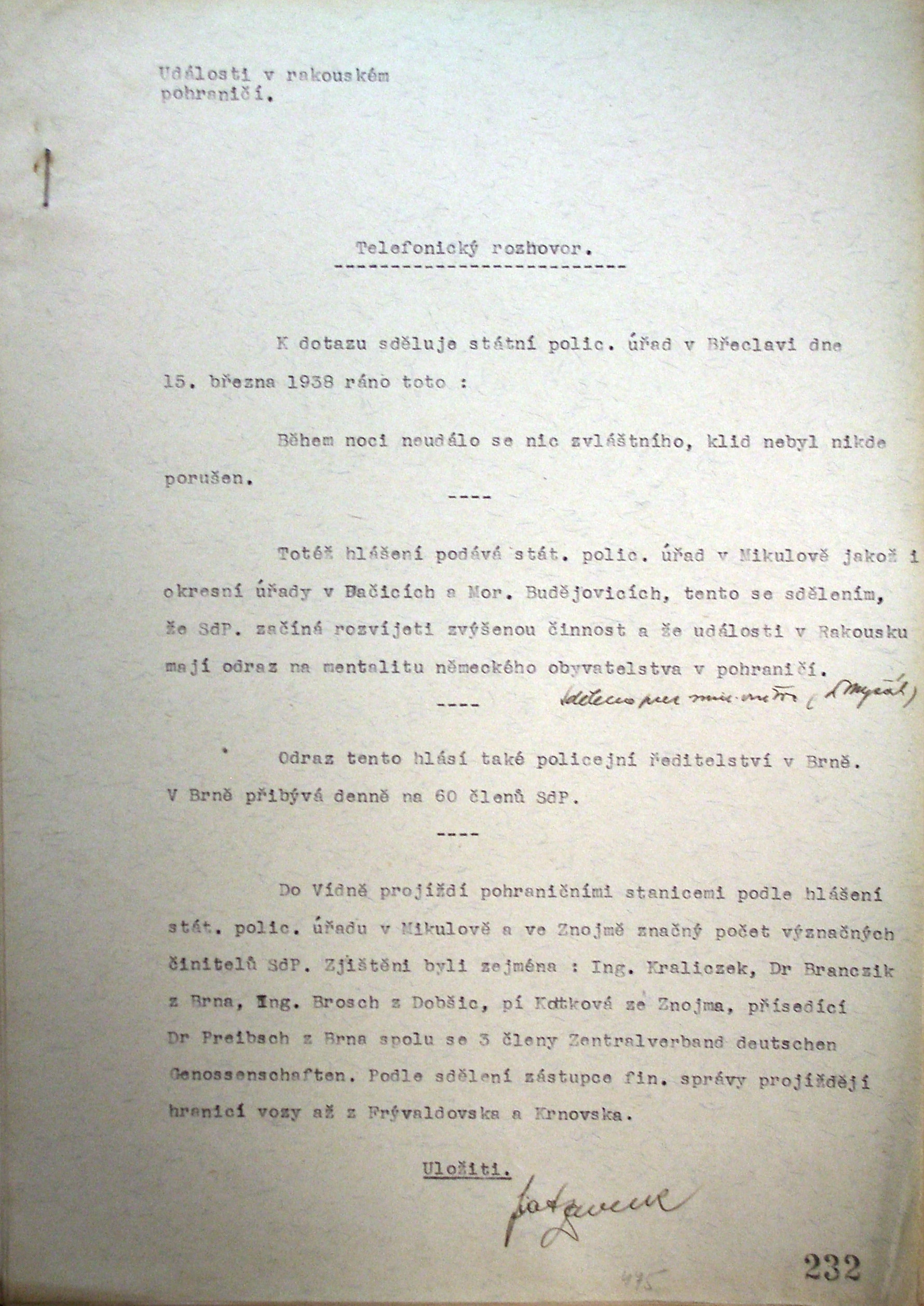

The so-called Anschluss of Austria to Nazi Germany in March 1938 marked the final turning point in the already eroded migration mechanisms in most European states.[1] The Czechoslovakian Ministry for Interior Affairs announced a general ban on any refugees from Austria on 11th March 1938. Many states such as the United Kingdom or Switzerland introduced compulsory visas for Austrian citizens and many of Austria’s neighbouring countries closed their borders to Jewish refugees. Documents like the “telephone messages to the regional authority in Brno on the activities at the Austrian border” offer an almost hourly protocol into events at the border after the Anschluss in 1938.

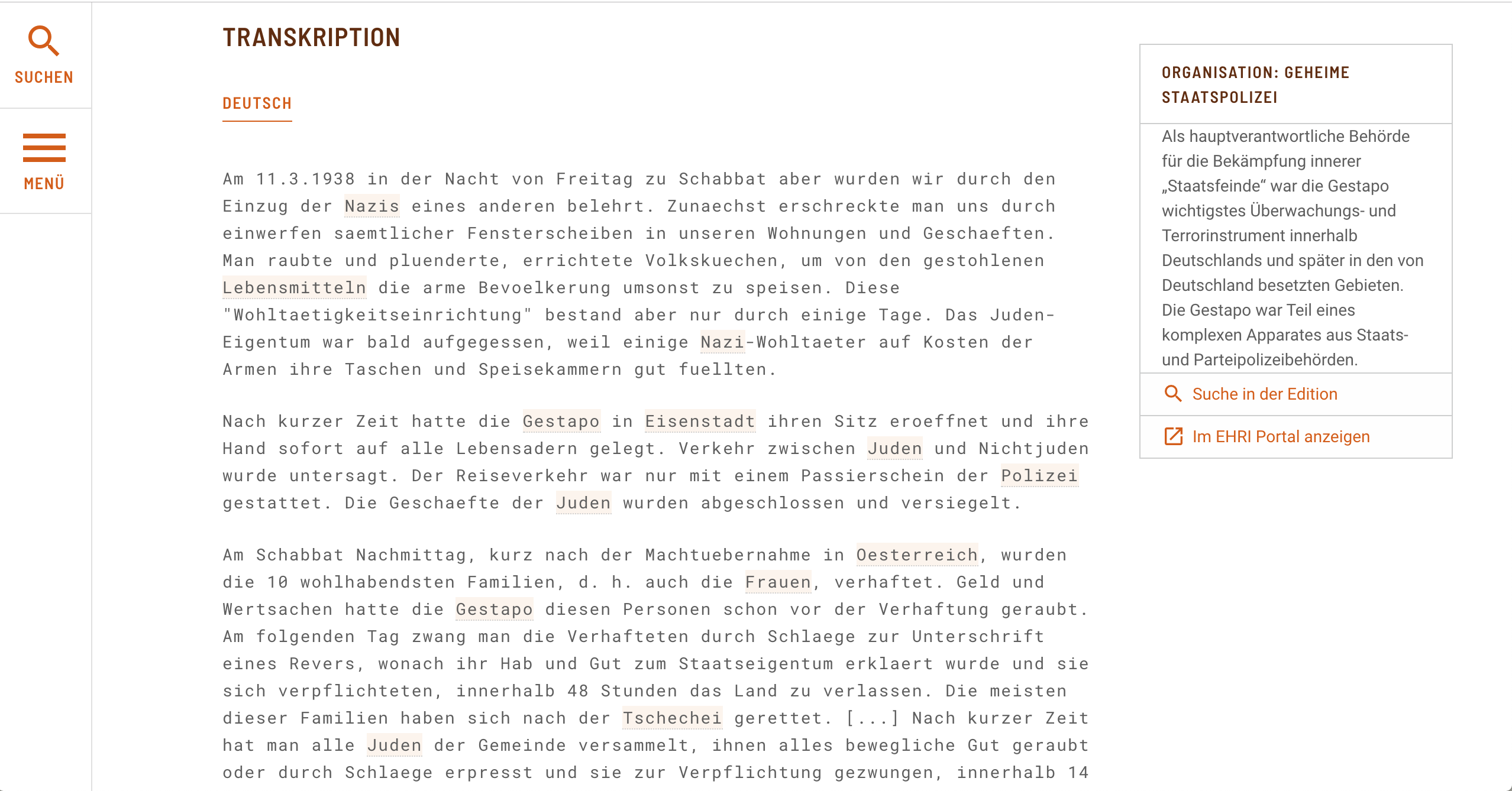

The Anschluss of Austria to Nazi Germany also marked the beginning of the mass expropriation, deprivation of rights, expulsion and murder of the Jewish population. The very night of the Anschluss saw National Socialists and Nazi sympathisers begin the arrest and humiliation of known opponents of the Nazi regime and Jews and the theft of their property. Foreign Jews or those without citizenship – especially those imagined as “Ostjuden” (Eastern Jews) – were often the first target of the state’s violence. As shown by several documents included in the BeGrenzte Flucht online edition, the Anschluss pogroms in many places led to the first instances of expulsions and mass flight of the Jewish population. A report by a board member of the Frauenkirchen Jewish community describes how the abuses suffered by the population directly after the Anschluss also led to their expulsion:

On the following day those who had been arrested were forced under threat of violence and actual violence to sign a declaration that all their property and belongings were now the property of the state and requiring that they leave the country within 48 hours. The majority of these families saved themselves by going to Czechoslovakia.2

Upon arrival in Czechoslovakia, the Jewish refugees became ever-more dependent on the help of charities and aid organisations for their daily needs, help with the authorities and preparation for further emigration. These organisations were mostly private committees for refugees that received little state support. The online edition features documents that show how Jewish refugees relied especially on the help of Jewish organisations and communities. Although these organisations were often supported by transnational Jewish organisations such as JOINT or HICEM, the funds often proved inadequate.

The Expulsion of the Burgenland Jews

The mapping of all the documents included in the online edition also shows how the Jews of the Burgenland, the border region between Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia, were treated as non-citizens3 and how small groups who crossed the nearby border into Czechoslovakia were deported to Hungary and Yugoslavia. All three neighbouring countries reacted by closing their borders and sending the refugees back.

The radical nature of the expulsions in the Burgenland and the restrictive character of the refugee policies in the neighbouring states is made especially clear in the case of the Jews of Kittsee and Pama. Forced from their homes during the night of 16th-17th April 1938 by the SA, they were brought to an island near to the Czechoslovakian village of Theben (Devín). The speed of the expulsion was emphasised in the recollections of Aron Grünhut:

„The refugees reported that they were taken directly from the Seder table to waiting trucks outside, without being allowed to take any extra food or clothing with them and were forced onto the island in the Danube.“4

The Czechoslovakian authorities allowed the orthodox Jewish community in Bratislava to provide the Austrian Jews with food, afterwards they were deported back to the Burgenland. Similar events occurred along the Austrian-Hungarian border, leaving some in terrible conditions in no-man’s land.

A series of documents relating to the expulsion of the Burgenland Jews shows how the orthodox community were finally forced to shelter the displaced Austrian Jews on a tugboat on the River Danube. It was only after four months and increased pressure from the Hungarian government 5 that aid organisations were able to arrange for the emigration of this group of refugees to Palestine and the United States in August 1938.

The archival material has also shown that in the following months, predominantly Jewish refugees and displaced people were strictly turned away at the border. In the spring and summer of 1938, the woods and meadows in South Moravia and the banks of the Danube on the border to modern-day Slovakia became the scene of an ongoing manhunt. The Czechoslovakian authorities sent thousands of refugees back the area of what had been Austria, regardless of whether they attempted to cross the border legally or illegally. A telegram from the Central Office for Refugee Aid in Brno (Brünn) sought help from the Czechoslovakian minister for interior affairs for 19 Austrian refugees who had crossed the border near Znojmo (Znaim) without papers. 6 The refugees were returned to the Austrian border by the police the following day.

Excerpts from interviews from the Documentation Centre of the Austrian Resistance (DÖW) and the Jewish Museum in Prague also show the individual actions of the border officials, who in some cases did not seek to actively stop people from successfully crossing the border.

The political changes brought about the “Munich Agreement” in September, and the German occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, ensured that Czechoslovakia would become only a temporary stop in their escape to further places of exile such as the United Kingdom, France, Belgium or the United States. Around 2300 Austrian refugees would later be deported from the “Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia” to the ghettos, concentration camps and extermination camps, something the edition also highlights using several documents relating to the fate of the Guttmanns, a married couple from Vienna.

* * *

The digital edition BeGrenzte Flucht illustrates how bringing together of archival and other documentation can foster research: it provides a new perspective on and across the border, allows to reinterpret the border zone as a space of interaction and to comparatively examine the refugee policies of European states.

Published in German with the help of the new EHRI tools for digital editions, it also demonstrates the benefits of critical documentary editions using the data of the European Holocaust Research Infrastructure to account for historical context. In the future, another contribution to the EHRI Document Blog will explain the technical and editorial procedure using the EHRI platform for digital editions.

* * *

Notes

- For detailed information about the Czechoslovakian policy towards refugees in the 1930s see: Kateřina Čapková und Michal Frankl, Unsichere Zuflucht: Die Tschechoslowakei und ihre Flüchtlinge aus NS-Deutschland und Österreich 1933-1938 (Köln: Böhlau, 2012). ↩

- Theodor Guttmann, Dokumentenwerk über die Jüdische Geschichte in der Zeit des Nazismus: Teil 1. Ehrenbuch für das Volk Israel. (Jerusalem: Awir Jakob 1943), 70-71. ↩

- Gert Tschögl, Barbara Tobler, und Alfred Lang, Hrsg., Vertrieben. Erinnerungen burgenländischer Juden und Jüdinnen (Vienna: Mandelbaum, 2004). ↩

- Aron Grünhut, Katastrophenzeit des slowakischen Judentums. Aufstieg und Niedergang der Juden von Pressburg (Tel Aviv: 1972), 13-16. ↩

- Kinga Frojimovics, I Have Been a Stranger in a Strange Land. The Hungarian State and Jewish Refugees in Hungary, 1933-1945 (Jerusalem: International Institute for Holocaust Research, Yad Vashem, 2007). ↩

- National Archives, Prague, presidium of the ministry of the interior (225) 1936-1940, Sign. X/R/3/2, box 1186-16. ↩