On the cold night of 31 December 1941 a group of about 150 young Jews crowded in the small kitchen of Vilna Ghetto, in Straszuna Str. No.2. They pretended to be celebrating the New Year’s Eve, to distract the attention of their German and Lithuanian guards, who were in the process of getting drunk.

The meeting was in fact held in memory of the Jews who were murdered in the past months in the forest of Ponary (Paneriai in Lithuanian, located approximately 15 kilometres south-west of Vilnius), and one of the survivors who escaped from the death pits was invited to give her testimony about her experience, having narrowly escaped death.

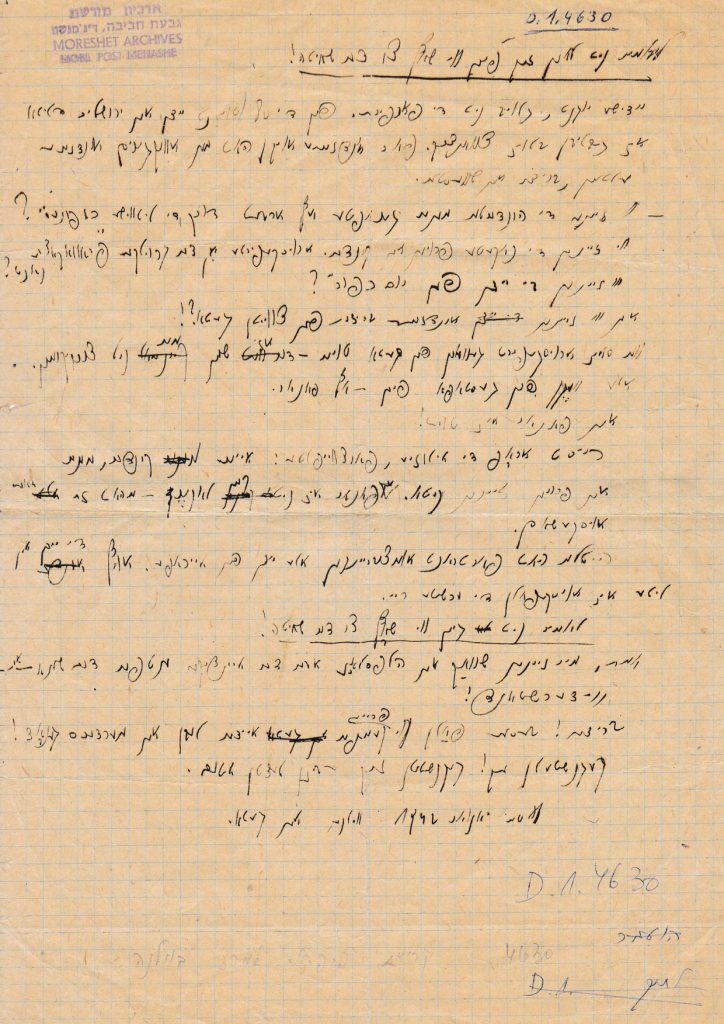

In the course of that evening a proclamation was read in Yiddish by Abba Kovner and in Hebrew by Tosia Altman. That proclamation symbolized the initial idea of resistance which started to bloom in the minds of those youth movement members, after experiencing the mass massacre of their Jewish brothers and sisters in Lithuania. The original document, handwritten in Yiddish by Abba Kovner, is preserved in the Moreshet Archive, located in Givat Haviva, Israel, under the archival number (symbolization) D.1.4630. The document was written at the end of 1941, in a Polish Dominican monastery near Vilna. The nuns of the monastery, under the guidance of Anna Borkowska, a Polish cloistered Dominican nun, who served as the prioress of this monastery, helped sheltered Jews. In 1984 Borkowska was awarded the title of Righteous among the Nations by Yad Vashem for her rescue efforts. Kovner, who was one of the founders of Moreshet brought to the archive this unique document, in addition to other original documents from Vilna Ghetto.

Please follow the link for the EHRI archive description:

Following is the proclamation’s English translation:1

Let us not be led like sheep to the slaughter!

Jewish youth, don’t trust those who deceive you. Of 80,000 Jews in

“Yerushalayim de Lita”2, only 20,000 are left. Our parents, brothers, and

Sisters were torn from us before our eyes.

Where are the hundreds of men who were seized for labor by

Lithuanians?

Where are the naked women and the children seized from us on the

Night of fear? Where are the Jews of Yom Kippur?

And where are our brethren of the second ghetto?!

No one returned of those marched through the gates of the ghetto,

All the roads of the Gestapo lead to Ponar.

And Ponar means death!

Those who waver, put aside all illusion! Your children, your wives,

Your husbands are no more. Ponar is no concentration camp. All were

Shot dead there.

Hitler conspires to kill all the Jews of Europe. And the Jews of

Lithuania has been picked at the first line.

Let us not go like sheep to the slaughter!

True, we are weak and defenceless, but the only answer to the murderer is resistance!

Brothers! Better fall as free fighters than to live at the mercy of the

Murderers! Rise up! Rise up until your last breath.January 1, 1942 Vilna ghetto

The Germans invaded Lithuania in June 1941 and just six months later, with the help of local collaborators, they massacred approximately 30,000 of its Jewish residents. The main execution site was in the forest of Ponary. The second wave of extermination came in late August 1941, when Hans Christian Hingst, the Gebietskommissar(regional commissar) of the Vilnius municipality received “Provisional Directives” from the Reichskommissar for the Ostland (commissar of the German Reich) Heinrich Lohse, which included continuing the extermination of the Jews, establishing the ghettos, and more.

The Germans sealed off the old Jewish quarter to serve as the location of the ghetto. On Saturday, 6 September 1941, the Jews of Vilna were forced into two ghettos, No. 1 was the larger and No. 2 was smaller. In October 1941 ghetto No. 2 was liquidated and most of its inhabitants were expelled to be murdered in Ponary.

The proclamation “Let us not be led like sheep to the slaughter!”, Vilna, German-Occupied Lithuania, January 1, 1942

The period between November 1941 and January 1942 was for many Jews who were imprisoned in the ghetto a time of seeking ways to grapple with the devastation and the mass murder surrounding them. Some sought ways to organize an active armed resistance against the Germans and their collaborators.

A secret meeting of Hashomer Hatzair youth movement members was held in the Polish Dominican monastery nearby Vilna in late December 1941, at which they decided to spread the word about what they believed was about to be the ultimate fate of the Lithuanian Jews, and in fact, of all the Jews in Eastern Europe – total annihilation. They asserted that the only way out of this horrific situation was to resist the Germans and their collaborators with weapons. Pursuant to the meeting they prepared to conduct a large gathering of youth movements’ members and read out loud the proclamation which summarized that idea.

The meaning of the phrase “Let us not be led like sheep to the slaughter”

This phrase comes from the Old Testament, the book of Isaiah, 53, 7. The original text reads:

He was oppressed and afflicted,

yet he did not open his mouth;

he was led like a lamb to the slaughter,

and as a sheep before its shearers is silent,

so he did not open his mouth.

The meaning is clear: to be led to death without any resistance. This phrase has a major role in collective remembrance of the Holocaust in Israel. During the first years of the young Israeli state (established in May 1948), many of the Holocaust survivors were looked upon as though they had been led to death by the Germans without any resistance. The emphasis was put on the ghetto fighters and the partisans, who had physically resisted the perpetrators with weapons in hand. They were seen as the “heroes”, as opposed to the “weak” and passive Jews who were expelled to death sites and concentration camps. However, later on and especially following the Adolf Eichmann trial which took place in Jerusalem in 1961-1962, when the voices of the survivors were heard, sometimes for the first time, the perception of the survivors as helpless victims emerged. The emphasis shifted from solely speaking about the armed resistance to addressing also the resilience. Those who did whatever they could in order to remain humans and survive during the most horrible period were then perceived as “heroes” as well. A mother managing to obtain some food for her starving children; a child risking his life by escaping through a fence to the other side of the ghetto in order to get a little food and sneak it back in; religious Jews still observing the Mitzvoth (rituals) in the ghettos and camps, etc.

In this context, of judgment, Primo Levi wrote:

“I believe that no one is authorized to judge them, not those who lived through the experience of the Lager and even less those who did not. I would invite anyone who dares pass judgment to carry out upon himself, with sincerity, a conceptual experiment: let him imagine, if he can, that he has lived for months or years in a ghetto, tormented by chronic hunger, fatigue, promiscuity, and humiliation; that he has seen die around him, one by one, his beloved; that he is cut off from the world, unable to receive or transmit news; that, finally he is loaded onto a train, eighty or a hundred persons to a boxcar; that he travels into the unknown, blindly, for sleepless days and nights; and that he is at last flung inside the walls of an indecipherable inferno”.3

I could not agree more with Levi’s painful words and believe that it is not our place to judge those who have been there. For many years Jews who did not actively fought back during the Holocaust were judged by others. For example, Litman Mor, a former FPO member in Vilna Ghetto and a partisan, testified: “When I came out of the partisan forests, I thought that the only ones who acted correctly were the partisans… I didn’t value the Jews who’ve been in the camps. I am ashamed to say it now”.4 In the case of the Jewish underground in Vilna Ghetto and the call of its young members to the entire population “not to be led like sheep to the slaughter”, the picture is more complicated as I will argue here.

Creation of the Underground Organization and its aftermath

Following the event of the reading of the proclamation, on 21 January 1942 the underground movement FPO (The United Partisan Organization, in Yiddish: Faraynikte Partizaner Organizatsiye) was established in Vilna ghetto. A meeting was held in the room of the leader of the Beitar youth movement in the ghetto, Joseph Glazman. The creation of this united underground movement was a unique phenomenon, as it was comprised of various youth movements that were active in the ghetto, and had decided, after much deliberation, to join forces. The underground was under the leadership of Yitzhak Wittenberg (1907-1943), and a command of four more representatives of the different movements.

The structure of the FPO underground organization command comprised of representatives from five youth movements:5

Mapping the structure was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

Initially its members were divided into clandestine cells of three members, “trios”, and four to five months later they formed cells of five members, “quintets”. At its peak, in April-August 1943, the FPO organization numbered approximately 300 members.

“Combat Regulations” were issued in March 1943, which addressed the structure of the underground, recruiting methods, orders and more. It contained instructions on how the organization should act in the event of the partial liquidation of the ghetto, discussions on why it was crucial to stay in the ghetto rather than escape to the forest and join the Soviet Partisan Movement, and more. They prepared themselves for armed resistance when the ghetto would be in danger of annihilation. They managed to obtain weapons and smuggle them into the ghetto.

After facing disagreements and struggles with the Jewish Judenrat (Jewish Council) and resentment from the ghetto inhabitants, who thought they could survive in the ghetto by working for the Germans, they started sending groups of FPO members to the forests surrounding Vilna.

On 23 July 1943, at night, the first group of FPO members, under the command of Joseph Glazman, escaped the Vilna ghetto to the Narocz forests, which are located on the border between Lithuania and Belarus. On 23 September 1943, the day of the final annihilation of the Vilna ghetto, the last members of the FPO, who had until then remained in the ghetto, escaped through the sewers pipes of the city, and arrived at the Rudniki forests, which are located approximately 40 kilometres south of Vilnius, where they joined the Soviet partisan units. And so, after vast preparations and expectations of underground organizations members to physically and actively resist the Germans, an armed revolt did not occur in Vilna Ghetto. Historian and Holocaust survivor Yitzchak Arad explains, that the FPO leaders did not initiate the armed revolt, because they had the opportunity to escape the forests, join the partisans, and continue the fighting against the Nazis from there. And thus the goal of fighting in the ghetto was not achieved.6 Over the years there have been objections and criticism of that decision, to escape and not to revolt, and even some accusations were raised against the FPO members’ decision to save themselves and abandoned the Jewish population of the ghetto.7

In the collective memory on the topic of active resistance versus passive resilience, the Ghetto underground members and the Jewish partisans are often being perceives as “heroes”, who fought and revolted against the enemy. However, few former partisans, who escaped to the forests – an act which held the opportunity of survival – had carried with them heavy “baggage”. Litman Mor recalled in his testimony that he was very disappointed to understand that the FPO commanders had decided in the last minute not to give an order to start the planned revolt in the ghetto, and instead escaped to the forests with their people: “The idea of the fighting exploded”, he says.8 In this context, the meaning of the proclamation and the call for resistance within the Ghetto was replaced with the idea of escape and try to find a different framework of resistance, in the partisans’ forests.

Notes

- English version from: Juergen Matthaeus with Emil Kerenji, Jan Lambertz, and Leah Wolfson, Jewish Responses to Persecution1941-42, Vol. 3, (Lanham, Md.: AltaMira Press, 2013), 339-340. See also: Yitzhak Arad, Ghetto in Flames: The Struggle and Destruction of the Jews in Vilna in the Holocaust (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 1981), 231-232. ↩

- East European Jews called Vilna “Jerusalem of Lithuania”, due to its prosperity and the richness of Jewish spiritual life. ↩

- Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), 59. ↩

- Testimony of Litman Mor in a partisans gathering, (19.1.1989), Jabotinsky Institute Archive, k7a-13/8/3, 11. ↩

- From the FPO command only two managed to survive the war: Abba Kovner and Nissan Reznik. The other three perished: Wittenberg in the tragic events of 16 July 1943, in the Vilna ghetto. He was turned over to the Gestapo and was found dead the next day; Chwojnik was captured in Vilna on 23 September 1943 following a failed attempt to escape the ghetto through the sewers pipes; and Glazman died in October 1943 in the partisan forests of Byelorussia in the course of combat with Germans. ↩

- Arad, Ghetto in Flames, 479. ↩

- For example, in April 1990 an article entitled “There was No Revolt in the Ghetto, was published in the Israeli Journal Yiton 77, by Yitzchak Zohar, a member of the FPO who waited for the command to start the revolt, but subsequently was captured by the Germans and sent to Labor Camps in Estonia. He argues that instead of the planned revolt the commanders of the underground decided to save themselves and abandoned their friends in the Ghetto. Yiton 77, No. 123, 26-27. ↩

- Testimony of Mor, k7a-13/8/3, 16. ↩

One Comment Leave a reply