For the past four years, I’ve been working with Harvard Law School’s extensive collection of documents from all 13 Nuremberg trials. My role is to create metadata for prosecution and defense exhibits (and source documents) so that future searchers will be able to find each item when the whole collection is online.

The collection has three parts: transcripts of the trial proceedings, thousands of documents used by the prosecution and defense, and the larger collection of source documents, many lesser known, collected as evidence but never introduced in the courtroom. We also have “staff evidence analyses” discussing each document’s implications for the prosecution team. In the course of my work, I come across fascinating items all the time.

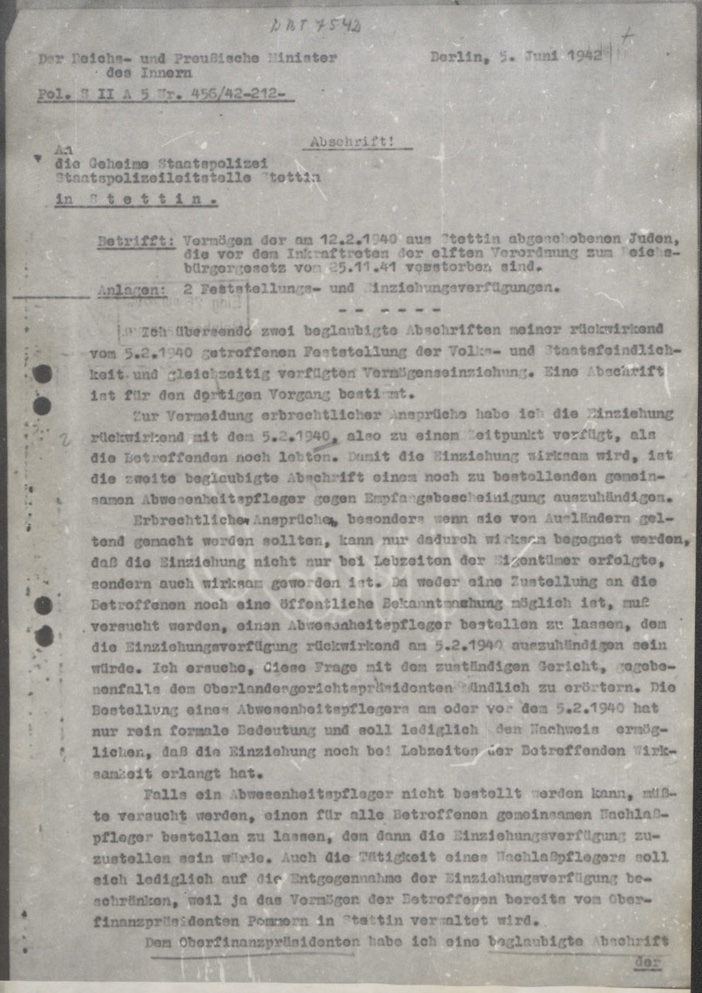

Document NG-5556, a letter written by SS official Rudolf Bilfinger to the Stettin Gestapo in June 1942, was not used in any of the trials. What struck me about it first was the attachment: an 11-page list of 280 deceased Jewish deportees. The list, which included birth dates, dates of death, maiden names and home addresses, exists in our collection only as a photostat. It is not clear who created the list; it might have been the Jewish Council in Lublin.

Bilfinger, the letter’s author, was an SS lawyer in Amt II-A (Organisation and Law) of the Main Security Office (Reichssicherheitshauptamt, or RSHA) in Berlin. His letter is a marvel of Nazi bureaucratic thought. It concerns the deportation of the Jewish community of Stettin (Szczecin), which occurred over two years earlier, in 1940. Before I discuss the letter, some background is needed on this deportation. Here’s what our documents have to say.

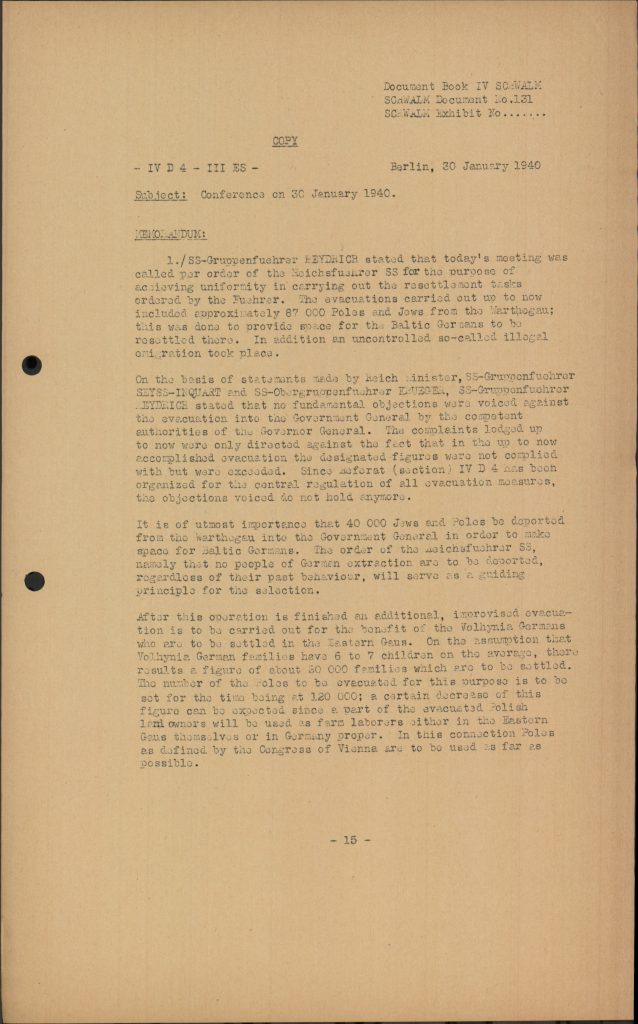

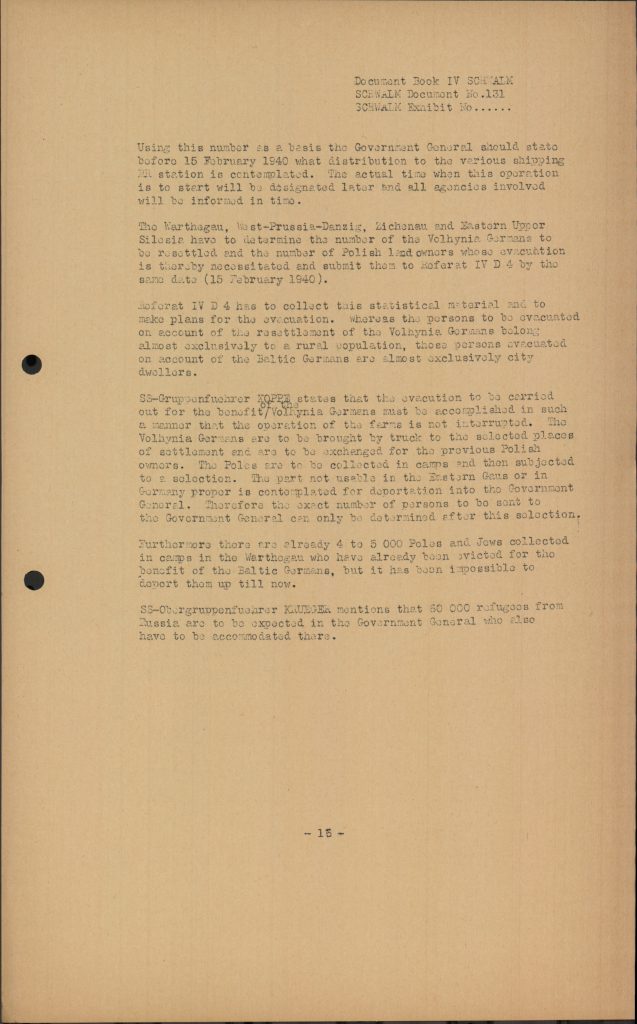

The first mention I’ve found of the Stettin deportation is in the minutes of a meeting (NO-5322) held in Berlin on 30 January 1940, almost exactly 2 years before the better-known Wannsee Conference. Security chief Reinhard Heydrich convened this 1940 meeting to plan for “resettlement” of Poles and Jews living in the Warthegau, an area annexed to the Reich after the invasion of Poland. Heydrich’s boss, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, had a grand vision of settling thousands of ethnic Germans from the Baltic region and Volhynia (an area in northwest Ukraine with many Volksdeutsche) into the Warthegau, necessitating the removal of that region’s inconvenient (and, to him, racially undesirable) residents. The meeting minutes state that 87,000 individuals had already been deported to the General Government in the five months since 1 September 1939; another 160,000 removals were pending.

Near the end of the meeting Heydrich brought up something unconnected to the Warthegau. “About the middle of February 1940,” he said, “1000 Stettin Jews whose apartments are urgently needed for war purposes are scheduled to be evacuated and also deported to the General Government.” (If he was thinking of giving those apartments to Baltic Germans, he did not say so.) He was, in fact, quietly announcing the first deportation of German Jews from original Reich territory (the thousands of Jews deported to Nisko a few months earlier had lived in Vienna, Ostrava and Katowice). Heydrich gave no reason for the Stettin event or its midwinter timing1, and the minutes record no reaction to his momentous announcement. But events two weeks later bore out his prediction.

Stettin, an ancient Hanseatic port town near the Baltic, had been home to roughly 2,500 Jews at the time of the Nazi takeover in 1933. About half emigrated over the next seven years. The record shows that the rest of them, just over 1,000 people, including the young, the elderly, women in advanced stages of pregnancy, and non-Jewish women married to Jews, were rounded up in the wee hours of February 12/13, 1940; this included seven members of the Borchardt family, pictured below in 1939 at a family gathering; one member of this family was to die in Lublin eight months after the deportation. Four days later, Alexander Kirk, chargé d’affaires at the US embassy in Berlin wired the State Department that nearly the entire Jewish population of Stettin had been removed from the city, and that the authorities in Berlin claimed they “were not consulted regarding this measure, which they attributed to the initiative of a local Party leader.”2

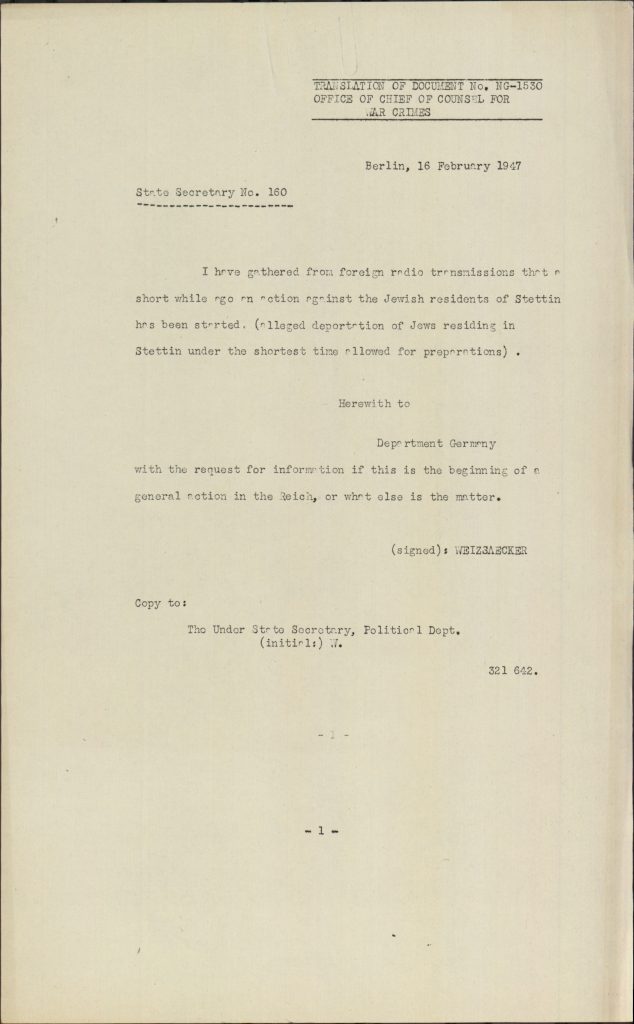

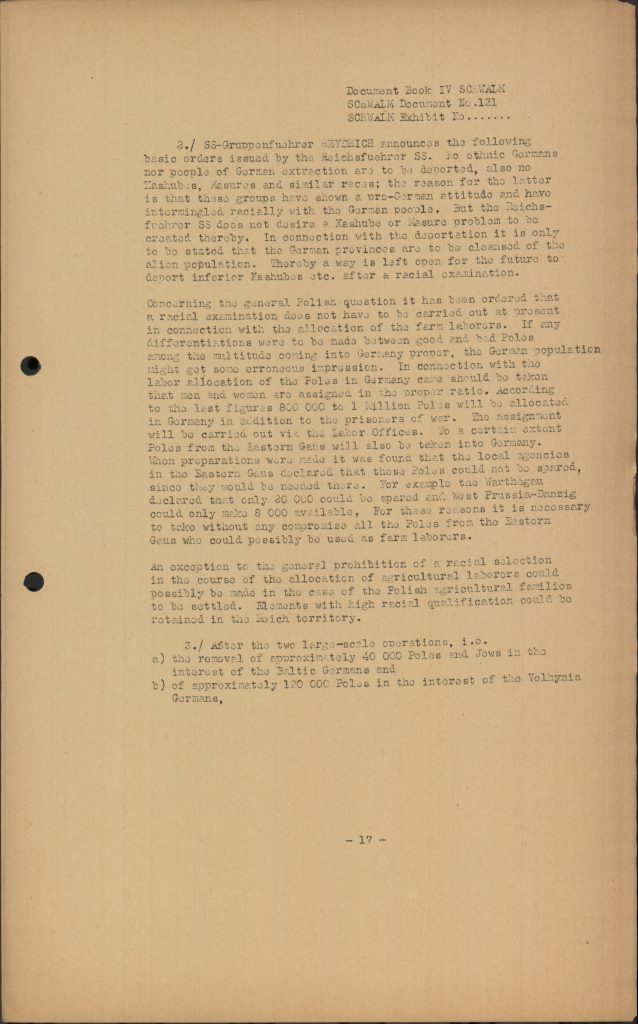

Document NG-1530. (click here for more information)

That same day, as revealed in Nuremberg document NG-1530, Ernst Weizsäcker, state secretary at the Foreign Office, heard about the Stettin deportation on the radio. Annoyed at being out of the loop, he asked the authorities to explain what was happening:

“I have gathered from foreign radio transmissions that a short while ago an action against the Jewish residents of Stettin has been started. . . request for information if this is the beginning of a general action in the Reich, or what else is the matter.”

The answer, if any, has not been found.

The mid-winter journey from Stettin to Lublin (a distance of 740 km) began on the 13th of February. According to Yad Vashem,3 after being rounded up in the middle of the night, deportees were assembled at the freight station in Stettin. (A chilling description of the complete collection process, found in a Russian archive, instructs teams of two Party members to arrive at each apartment at 8pm, put all Jews into one room, collect valuables, assist with packing, deal with pets, extinguish stoves, turn off gas and water, collect keys, etc.4) Once at the freight station, Stettin residents were joined by Jews collected from nearby towns. They were given minimal provisions but no water, and loaded into unheated passenger cars with insufficient seats for everyone. Upon arrival in Lublin on the 16th, “the deportees were marched in lines of four on unpaved roads in extreme winter conditions” to the Lipowa concentration camp 2.5 km away. From there they were taken by horse-drawn sleds to small towns in the region (including Głusk, Bełżyce, Piaski) where local Jews took them in (some sources5 state that able-bodied men were forced to walk several kilometers). Several were brought to the Lublin ghetto or local hospitals. The Lublin Jewish council was given responsibility for the new arrivals.

Between the dismal conditions of the transport, the winter cold, and the harsh accommodations in Poland, many people died that month. Some died on the trip itself; three corpses were offloaded en route at Schneidemühl, and at least ten people died in hospital in Lublin later that day.6 (82 of the deportees had resided in old age homes in Stettin, some were brought to the train station on stretchers.). Historian Leni Yahil states that 230 of the deportees died within the first month alone.7 The elderly were particularly likely to succumb; most individuals on Bilfinger’s list had been born between 1850 and 1880. (Several on the list shared two street addresses; these were likely the Jewish old-age homes referred to in the Yad Vashem article.)

But what was the purpose of the list? Why did it include only those who’d died prior to 25 November 1941? Unsurprisingly, Bilfinger’s concern was not with the high death rate. He was focused on the deportees’ assets. Despite what Heydrich had said back in 1940 about apartments being urgently required for war purposes, these residences had in fact been sealed, with belongings liquidated and proceeds moved to blocked accounts.8 The key event leading to Bilfinger’s letter was the passage on 25 November 1941 of the 11th Decree to the Reich Citizenship Law, stipulating that Jews living outside the Reich had forfeited both German citizenship and their assets, which could now be seized by the German government. (For these purposes, the Generalgouvernement – where Lublin was located – was not considered part of the Reich.)

Official correspondence described in Nuremberg documents (listed at end of article) shows that the German administration had been struggling with the question of how to apply this new law to those who’d inconveniently died before its passage. Their solution: to retroactively declare those 280 Stettin Jews as “Staatsfeinden” (enemies of the state), thus enabling seizure of assets.9 But that wasn’t enough. Stretching the legal envelope, Bilfinger postdated the official seizure of assets to 5 February 1940, “a time when the persons concerned were still alive.” Since these persons could not be notified, he suggested that a trustee be appointed to receive the official order of confiscation. To top it off, his letter to the Stettin Gestapo was written on the letterhead of the Reich Ministry of the Interior (an interesting detail noted by Susanne Heim in her discussion of this document).10 Related 1942 correspondence between the Reich Ministry of Finance and the Main Security Office discusses the vexing problem of how to seize assets of Jews who “have avoided deportation by suicide.”11

This story, of course, ends unhappily. Many of the Jews in Lublin were killed in 1942 as part of Aktion Reinhardt. In November 1943, the Lublin ghetto was cleared as part of Aktion Erntefest; any remaining Stettin Jews were sent to extermination camps and murdered at this time. I was able to locate letters and memoirs of only a handful of survivors from this group.12

These documents leave many questions unanswered. Why was Stettin chosen for the first deportation of Jews from Germany proper? How were the deportees tracked in Poland? Who collected names and dates of death to pass on to the Main Security Office in Berlin? What happened to the assets of the deportees who had not died by November 1941? (One assumes those assets would have been confiscated shortly after the passage of the new law, but this information is not in these documents.) What happened to the children in the Jewish orphanage, noted by Yad Vashem to have been excluded from the 1940 deportation?

A larger, perhaps deeper question remains. How are we to understand the behavior of the Stettin authorities, who, immediately after implementing this brutal, inhumane roundup and deportation, dutifully sealed off hundreds of apartments, sold the contents, and then sequestered the proceeds for over two years, rather than simply helping themselves to all of this in the weeks after the residents had been “shoved off”? (Abgeschoben, the verb found in the subject line of Bilfinger’s letter to the Gestapo—the past participle of abschieben, to deport—comes from the same root as the English word shove.)

Sadly, all of this remains relevant eighty years later. Reading through the 1940 Danish news article mentioned in footnote 4, I came across this quote:

“It is to be assumed that the (US) State Secretary Sumner Welles, during his visit to Berlin in early March, will bring up these inhuman incidents with Herr von Ribbentrop, the head of the Foreign Office.”

The writer goes on to mention how inconsistent the Stettin deportation is with earlier negotiations between the US and Germany regarding a planned, orderly emigration of German Jews. With a change of names and places, this piece could easily be commenting on any of several contemporary situations. The ability of one nation to restrain another nation intent on committing atrocities remains as limited as ever.

Bilfinger, the author of the letter that inspired this essay, lived a long life, dying in 1996 at age 93. After leaving occupied Poland, he headed up an SD Einsatzkommando in Toulouse in 1943. He was arrested in 1945, turned over to the French, and tried in 1953 for his activity in France, sentenced only to “time served.” He returned to civil service in West Germany but was suspended in 1965 under threat of exposure of his activity in the SS. How he spent the last three decades of his life is unknown.

I would like to thank the following individuals for assistance in preparing this essay: Professor Bradley Nichols, University of Missouri, Susanne Heim and Andrea Löw, Institut für Zeitgeschichte, Munich – Berlin, Andrew Haggarty, Goddard Library, Clark University, Massachusetts, Michael Miller, moderator of forum.axishistory.com, Ralph Anton of deutsche-schutzgebiete.de, Winfried Garscha of DÖW, Vienna, The Wiener Holocaust Library Collections Team, and Paul Deschner of the Harvard Law School Library.

Bibliography

Books:

Adler, H.G. Der verwaltete Mensch. Studien zur Deportation der Juden aus Deutschland. Tuebingen: Mohr-Verlag, 1974.

Frank, Jacob and Mark Lewis. Himmler’s Jewish Tailor. Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2000.

Heim, Susanne, and Maria Wilke. Die Verfolgung und Ermordung des europäischen Juden. Band 6: Deutsches Reich und Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren, Oktober 1941 – März 1943. Oldenbourg: De Gruyter, 2019.

Löw, Andrea, et al. The persecution and murder of the European Jews by Nazi Germany, 1933-1945 Volume 3, German Reich and Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, September 1939 – September 1941. Berlin, Boston. De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2020

Mendelsohn, John. The Holocaust: Selected Documents in 18 Volumes. Volume 2: Legalizing the Holocaust, the Later Years 1939-1945. New York: Garland Publishing, 1982.

Mendelsohn, John. The Holocaust: Selected Documents in 18 Volumes. Volume 8: The Deportation of the Jews to the East. New York: Garland Publishing, 1982.

Peiser, Jacob and Lionel Kochan. Die Geschichte der Synagogen-Gemeinde zu Stettin. Eine Studie zur Geschichte des pommerschen Judentums. Würzburg: Holzer-Verlag, 1965.

Silberklang, David. Gates of Tears: The Holocaust in the Lublin District. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2013.

Wilhelmus, Wolfgang. Juden in Vorpommern. Schwerin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Landesbüro Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, 2007.

Yahil, Leni. The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1991.

Websites and Articles:

“Statistik und Deportation der jüdischen Bevölkerung aus dem Deutschen Reich. Stettin nach Lublin.” This definitive article is accompanied by images of relevant documents, including a longer list of deceased deportees, as well as the complete 32-page list of all deported Stettin Jews (including full names of the parents of each deportee as well as the mother’s birth name).

“Transport from Stettin, Pomerania, Germany, to Lipowa Camp, Poland on 13/02/1940.”

Survivor Accounts:

Eyewitness account by Elsa Meyring, Stettin, of her experiences of the deportation of Stettin Jews to Lublin Ghetto.”\ Wiener Library, London. (Elsa was allowed to leave Lublin as she had official papers allowing her to emigrate to Sweden.) See Abstract.

Story of Mosbacher family of Stettin.

List of Nuremberg documents related to extraction of assets of deported Jews:

- NG-1530: communication from Weizsäcker inquiring about Stettin deportation

- NO-5322: Minutes of meeting held 30 Jan 1940 to discuss deportations of Poles and Jews from the Warthegau

- NG-5371: 1942 Finance Ministry correspondence re extracting sequestered assets of Jews who had committed suicide “to avoid deportation”

- NG-5368: 1942 Finance Ministry correspondence re confiscation of assets of deported Jews who had died prior to passage of 11th Ordinance

- NG-5556: Bilfinger’s June 1942 letter to Stettin Gestapo with list of deceased Stettin deportees

- For an in-depth discussion of this conference and the deportation itself, see “Statistik und Deportation der jüdischen Bevölkerung aus dem Deutschen Reich. Stettin nach Lublin,” http://www.statistik-des-holocaust.de/list_ger_brb_400213.html.

- Mendelsohn, John. The Holocaust: Selected Documents in 18 Volumes. Volume 8: The Deportation of the Jews to the East. New York: Garland Publishing, 1982, page 5.

- “Transport from Stettin, Pomerania, Germany, to Lipowa Camp, Poland on 13/02/1940,” yadvashem.org, https://deportation.yadvashem.org/index.html?language=en&itemId=10500862&ind=-1 The narrative includes a moving description of the deportation written by an anonymous survivor.

- Loew, Andrea, et al. The persecution and murder of the European Jews by Nazi Germany, 1933-1945 Volume 3, German Reich and Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, September 1939 – September 1941. Berlin, Boston. De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2020, page 177, document 52.

- Yahil, Leni. The Holocaust: The Fate of European Jewry. New York: Oxford University Press, 1990, page 138.

- “Deutschland deportiert Staatsangehörige,” Politiken, Copenhagen, 17 Feb 1940. http://www.statistik-des-holocaust.de/Stettin-1.jpg (accessed 16 February 2021).

- Yahil, The Holocaust, 138.

- Mendelsohn, John. The Holocaust: Selected Documents in 18 Volumes. Volume 2: Legalizing the Holocaust, the Later Years 1939-1945. New York: Garland Publishing, 1982, page 131.

- The 1933 law authorizing such seizures is explained on this webpage: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gesetz_über_die_Einziehung_volks-_und_staatsfeindlichen_Vermögens.

- Heim, Susanne. Die Verfolgung und Ermordung des europäischen Juden. Band 6: Deutsches Reich und Protektorat Böhmen und Mähren, Oktober 1941 – März 1943. Oldenbourg: De Gruyter, 2019, p. 373.

- Nuremberg document NG-5371, introduced by prosecution in Trial 11 (Ministries/Wilhelmstrasse trial) on transcript page 23905.

- Among this group were Manfred Heymann, Elsa Meyring, and Dr. Erich Mosbach and his wife. Elsa M. was allowed to emigrate to Sweden as she had a visa permitting this. See bibliography for details, in particular Wilhelmus, Wolfgang. Juden in Vorpommern. Schwerin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Landesbüro Mecklenburg-Vorpommern, 2007.

Kylie Thomas

Thanks for your careful research and also for linking the history you detail here to questions of impunity and ongoing injustice in the present.