“In July 1944, following the order of Mengele, I was taken to the revier of the Gipsy lager. On the third day I was put to sleep and taken to the surgery. Sometime later I woke with terrible belly- and backpain. Three weeks later the anesthesia was repeated. Then I was in hospital for 4–5 days. A Greek doctor, dr. Kohan, working for Mengele, helped me get back to C Lager.”1

In her compensation claim submitted to the government of the Federal Republic of Germany, Magda E. described the medical experiment conducted on her, as a result of which she suffered from various symptoms even years later: her menstrual period was irregular, she had constant belly- and back pain, and, most importantly, she remained infertile. All these, and the treatment she had received were described in and thus verified by the medical papers attached to her application.

How could it happen then, that even though her health had been impaired and the result had serious and permanent impact on her life, still she did not receive any compensation from West Germany? The archival material of her case as well as other compensation applications may shed light on some of the characteristics of the compensation process which took place in Hungary in the 1960s.

Please follow the links for the EHRI description of the institution and the collection description in the EHRI Portal:

Sources related to the West German compensation are held at the Hungarian National Archives, among the documents of the Financial Institutions Administration, Department of Indemnification, fond XIX-L-20-o. These sources have hardly been used in literature about the Hungarian Holocaust before. Each file contains the material of one individual: questionnaires, testimonies, protocols, internal correspondence, medical papers, etc. The questionnaires include detailed personal information concerning both the persecution and the post-war life. This article introduces one specific case, which involved the applications of two survivors: Magda E. and Mrs. Jenő S. While analyzing their compensation claims, certain specificities of this type of source need to be kept in mind. Firstly, in order to receive financial support from West Germany, the survivors emphasized – or, on the contrary, silenced certain issues in their testimonies; therefore, these texts need careful reading between the lines. Second, the vast majority of the applicants were women who had been sterilized. Their experiences had been painful and humiliating, and recalling them again, being interrogated, moreover, subjected to medical examination, was often hard to endure emotionally. Sometimes this resulted in false or blurred details in the narratives. The fallibility of human memory must also be taken into account, as the compensation process took place almost two decades after the events. Last but not least, the nature of the compensation itself calls for scrutiny: basically, the honesty of the survivors was tested, the damages they endured were classified. Since money was involved, the process itself implied that a certain sum can pay off for these damages; and the survivors were put into a position where they seemed to be “extracting” money from West Germany.2

In any case, the sources of the compensation are rich in data concerning the pre- and postwar life of survivors, and tell a lot about their self-representation and the strategies of constructing a narrative. The two compensation claims here are investigated from this latter point of view: how did the survivors adapt their descriptions to the expectations; how does it become clear whether an applicant intentionally or unintentionally distorted her narrative, or, horribile dictu, made up the whole story in order to get compensation? And what happened if they did?

Compensation for the victims of medical experiments

Mainstream Holocaust narratives tend to focus on the various aspects of anti-Jewish persecution, ghettoization, deportation and mass murder, and thus the post-war life of the survivors, restitution and compensation are often overshadowed or neglected. Investigating the restitution process, though, may uncover valuable information concerning the imprints the Holocaust left on the survivors’ life trajectories, and of course the attitude of the states which decided on the compensation measures.

After the Second World War, two main laws were introduced in West Germany, which aimed to integrate and unify the previous local restitution laws of the German states. The Bundesentschädigungsgesetz (BEG, Federal Indemnification Law) was enacted in 1953: this law secured compensation in the form of annuities for survivors who had suffered damage to physical integrity, health, freedom, professional interests, while the Bundesrückerstattungsgesetz (BRÜG, Federal Restitution Law), brought in 1957, provided restitution for confiscated estates and material damage. However, only those were enabled to apply, who had lived in German territory before 1953, moreover, compensations were to be paid only in those countries which had diplomatic relations with West Germany. This, obviously, excluded socialist Hungary.

Despite this, the leadership of the Hungarian Socialist Workers’ Party aimed to achieve compensations to be sent to Hungary, mainly out of economic interests – this manifested later when the compensation sums sent to the survivors were exchanged at an official, low rate and thus the state managed to withhold 1/10th – 1/8th of these sums. In 1957, the government established the National Committee of Persons Persecuted by Nazism (Nácizmus Magyarországi Üldözötteinek Országos Érdekvédelmi Szervezete, hereafter referred to as NÜÉSZ), whose task was facilitating the compensation and mediating between official bodies and the survivors.

In 1960, the West German government decided to extend the compensation program of the victims of pseudo-medical experiments to countries with which the state did not have diplomatic relations. As a result, and following the NÜÉSZ’s and the Hungarian government’s diplomatic and legal efforts, a call for compensation claims could be published in the biggest newspapers of the era, in the beginning of the 1960s.

The compensation applications of victims of Nazi medical experiments were administered by the Hungarian and International Committees of the Red Cross, the NÜÉSZ and the Financial Institutions Administration, on behalf of the government. The NÜÉSZ, which mostly consisted of Holocaust survivors itself, was the first to evaluate the applications. Then they were cross-examined both through the claimant’s medical examination by the appointed independent doctors, and the investigation of historical sources (for instance data was requested from the International Tracing Service); if necessary, witnesses were cited. The collected material was then sent to Geneva, to the International Committee of the Red Cross, which mediated towards the German government. After hearing every party involved, they decided on whether an applicant was eligible for financial support. Therefore, the survivors often received the compensation only years later, which sum was most frequently between 30 and 40.000 Marks. Those who learnt about the possibility too late or whose claim was not supported by the Red Cross, often received a certain sum from the NÜÉSZ.

The compensation claims of Magda E. and Mrs. S.

Magda’s widow mother lost her life in Auschwitz, while her sister, Klára died in Ravensbrück. When she returned, Magda had to stay in hospital in order to recover and she maintained herself with the Joint’s help. Later on, she found a position in a shop. Magda applied for compensation in 1963. In her testimony, she stated that she had been experimented on in anesthesia, and she had been helped by a Greek doctor, a certain Kohan, who had sent her back to the camp and thus prevented further experiments to be conducted on her. Since her return to Hungary, Magda had been suffering from various symptoms, and her infertility led her to decline her suitor, “as she knew that due to her illness, she could not give birth to a child.”3

As a result of the application and the initial investigation of NÜÉSZ, the conclusion of the experts was that “we are facing a gynecological type of experiment.” When interrogated again, Magda referred to a witness, Mrs. Pál B., whose testimony was taken some days later: she said that she had witnessed when Magda had been chosen for the experiment.

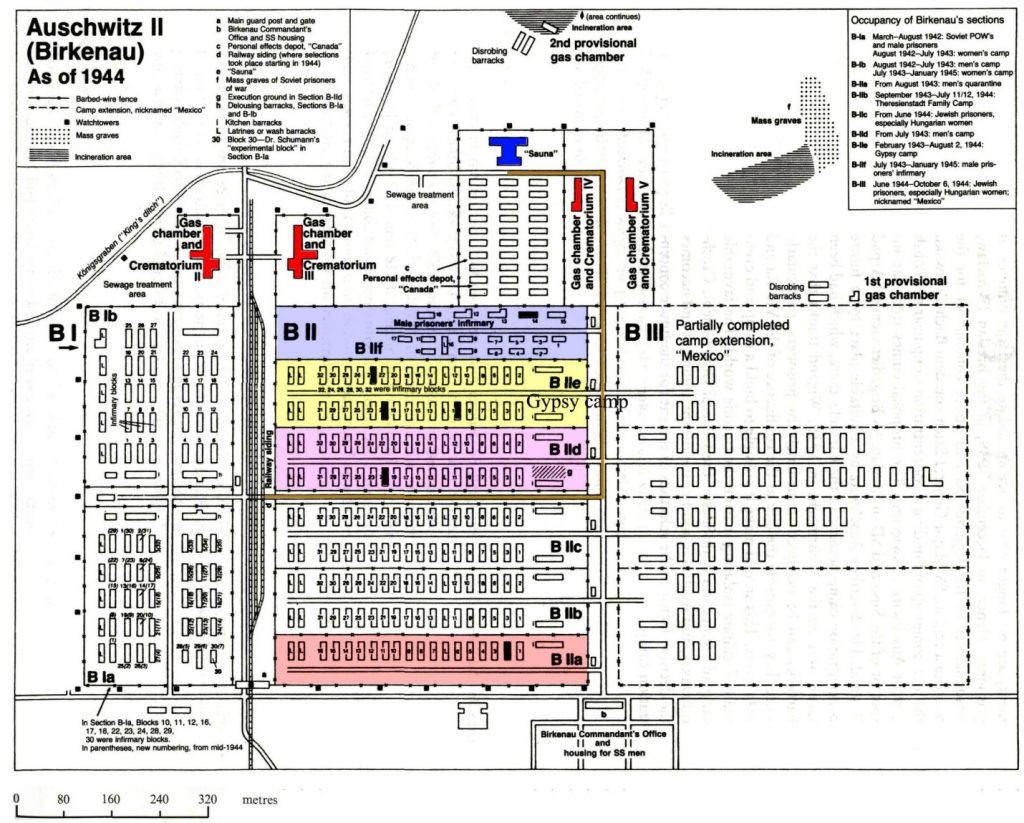

Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Simultaneously, Mrs. Jenő S. also handed in a compensation claim. Mrs. S. was born in 1921 and she was deported to Auschwitz with her family, where she lost her parents. Their house in Pestszenterzsébet was robbed, and when the woman returned, she also received aid from the Joint to restart her life. In her application, Mrs. S. described what had happened to her: “Mengele picked me and they took me to a hospital, where they conducted various examinations, among others, they took liquid from my neck, and then ca. 7–8 days later I was narcotized during a gynecological examination. Afterwards I woke with horrible head- and bellyache. They repeated this once more.”4 According to her medical certificates, Mrs. S. suffered from headaches which were being treated even during the time of her application. Additionally, she miscarried twice and after finally giving birth to a boy, she never managed to get pregnant again.

Conflict and Confrontation

In 1964, the members of the International Red Cross asked for confirmation from the ITS – however, no trace of Magda K. (Mrs. S.’s maiden name) could be found. A medical examination was then conducted at the Péterfi Sándor hospital, and according to the diagnosis of the independent doctor, in the case of Mrs. S. “causality between the decline of ability of reproduction and the pseudo-medical experiment can be verified without doubt.”5

Stuck between two conflicting expert opinions, the NÜÉSZ and the Red Cross took another testimony from the woman. The testimonies of Magda E. and Mrs. S. show striking similarities: the method of selection, the description of the experiment and its effects, and the way the two women escaped further experiments. Namely, Mrs. S. also stated that she had been saved by a certain dr. Kohan. In reality, Leon Cohen was a Greek Jew, who had worked as a merchant before his deportation. In May 1944, he was assigned to the Sonderkommando of Crematorium III in Birkenau; his task was ripping out the gold teeth of the gassed victims. Even though he was referred to as a “dentist”, he did not have qualification in medical studies. He acquired reputation in the camp as he took part in the preparation of the Sonderkommando uprising, but he never worked together with Mengele.6 This points to two things: 1, the testimonies of the two women were questionable, with at least one unlikely or rather untrue element and 2, even at this stage there were customary narratives, “good practices,” which could be used in order to make the story credible in the eyes of the committees (including that of NÜÉSZ, consisting of Holocaust survivors).

In August 1967, Mrs. Dezső F. asked for hearing at the Financial Institutions Administration and stated that both Magda E.’s and Mrs. S.’s compensation claims were unfounded. As a result, an internal investigation was conducted: one corrupted case could threaten the success of all other compensation claims, after all. At first, the members of the institution wanted to persuade the two women to withdraw their applications – by this time, those were ready to be sent to Geneva. The note written about the case mentions that “we should warn them to keep total confidentiality and in case they still get the compensation sum, they should use it with utmost care, without splurge, and in instalments because the Germans can reclaim it later.”7 This tone and expressions, as well as the lack of surprise suggest that the committee was aware that the testimonies were false. It did not even occur to them to take legal steps – not only because they were afraid of a potential scandal, but also because they knew that this was not the only case of false applications.

On December 5, 1967, a committee set up by the Red Cross and the NÜÉSZ held a meeting in order to clarify how to proceed with the case. The members, András Sz. (NÜÉSZ), Imre P. (Red Cross) and dr. Pál B. questioned Mrs. F. and Mrs. S. in the presence of a representative from the Financial Institutions Administration. According to the minutes of the meeting, Mrs. S. had to tell her story again, and the members asked her whether she had any enemies. It turned out that Mrs. F.’s sister knew about the application, and the basis of the bad relationship between the two women was that “we are in much better financial conditions. My husband is a self-employed tailor, her husband is a plumber, that’s why they envy us.”8

Thus, this might have been one of Mrs. F.’s motivations for denouncing Mrs. S. In order to get a more nuanced picture, the committee then questioned Mrs. F. She firmly stated that she had been deported together with Mrs. S. and they had remained together, i.e. Mrs. S. had never been separated for experiments. “Finally, Mrs. F. said that she did not want Mrs. S. to not get money, but she wanted to get some too.”9

She also admitted that one of the members of NÜÉSZ offered her to facilitate the processing of her application in case she handed in one, however, she did not have any political backwind with the doctor who gave the medical certificates. The committee members, with similar openness, told her that she should have applied anyway and a way would have been arranged.

This conversation demonstrates that the entire process of the compensation was corrupted: each institution knew about it, and doctors, experts all cooperated in silence. It was also clear at this point, that Mrs. S.’s application was false and everyone knew about it. The committee still had to make a decision; therefore, they confronted the two women. The following conversation evolved:

“András Sz.: Is it possible that you were separated from the K. girls [Mrs. F. and her sisters] for a longer time?

Mrs. S.: It is possible.

Mrs. F.: She was not away even for five minutes.

Sz.: So who remembers correctly?

Mrs. F.: I can bring five witnesses to prove that she was not away even for five minutes.

Mrs. S.: I can also bring witnesses.”10

Click here to view the whole transcription of the protocol

The role of witnesses was thus undermined; and the impossibility of reconciliation was established. The patience and empathy of the committee members is explained by Sz.’s words: “We, who were deported, we know what it means and all those unfortunates who went through it, should be compensated. Investigating this case, Mrs. S.’s damaged health can be demonstrated. If this, as Mrs. F. states, is not the result of an experiment, but Mrs. S. was more resourceful or bold, and thus she would still get money, who is put into a disadvantageous situation? The German state. Who should pay to Mrs. F.? Mrs. S. read an announcement, and applied, Mrs. F. should have applied too.”11

One day after the hearing, Mrs. S. admitted to dr. B. that she had not been experimented on, but she agreed with Magda E. that they would apply – which explains why their fabricated stories were so similar. By this time Magda E.’s application had been rejected by the International Red Cross, as they “could not ascertain that [she] was subjected to a medical experiment.”12 In the beginning of 1968, the committee decided not to bring forward their cases anymore. Nevertheless, both women received a 50.000 Forint aid in 1971, on the basis of “taking into account humanitarian aspects.”13

Conclusion

The compensation processes of Mrs. S. and Magda E. illuminate the most essential psychological, financial and political characteristics of compensation. The survivors justly felt that they should be compensated for their experiences during the Holocaust, as well as its long-term consequences, even if the compensation program targeted only people who had been experimented on. Here it must be emphasized that in Hungary the restitution of stolen or confiscated properties was poorly organized in the post-war years, and there was no extensive compensation program whatsoever, thus this was the first occasion that the survivors could get compensated.

False applications were supported by the organizations which mediated the applications – out of empathy and understanding, and sometimes also due to the political connections of the applicant. The question emerges, on which basis were the decisions made: did it turn out in every case whether an experiment took place? How much did political considerations, the privileged situation of an applicant or possibly bribery play a part? The compensation sum was big enough to motivate survivors to apply even if they were not eligible, and it was also big enough to cause ruptures in families as it could invoke jealousy and envy or the feeling of injustice, as it happened with Mrs. F.

On the other hand, the compensation was a legal step long overdue and an important financial asset for the survivors who needed healthcare. Were there survivors who applied even without being eligible? Were their applications supported by the mediating organizations? Should they be judged because of that? Did not every survivor who had been deported to a Nazi camp, gone through its horrors, lost relatives and health, deserve compensation from the German state?

- Magda E.’s testimony in her compensation claim file. Due to the sensitivity of the topic, the names in this article are anonymized. Magyar Nemzeti Levéltár Országos Levéltára (Hungarian National Archives, hereafter referred to as MNL OL) XIX-L-20-o, Pénzintézeti Központ, Kártalanítási Osztály (Financial Institutions Administration, Department of Indemnification), 4-200348, file of Magda E.

- Danieli, Yael: Massive Trauma and the Healing Role of Reparative Justice. In: Ferstman – Goetz – Stephens (eds.): Reparations for Victims of Genocide, 57.

- MNL OL XIX-L-20-o, 4-200348, file of Magda E.

- MNL OL XIX-L-20-o, 4-200655, file of Mrs. Jenő S.

- Ibid.

- See his memoir: Leon Cohen, From Greece to Birkenau, the crematoria workers’ uprising (Tel Aviv: Salonika Jewry Research Center, 1996), and: Gideon Greif, We Wept Without Tears: Testimonies of the Jewish Sonderkommando from Auschwitz (New Haven–London: Yale University Press, 2005), 286–309.

- MNL OL XIX-L-20-o, 4-200655, file of Mrs. Jenő S.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- MNL OL XIX-L-20-o, 4-200348, file of Magda E.

- Ibid. and 4-200655, file of Mrs. Jenő S.

Ruth J. Weinberger

Borbála Klacsmann correctly questions reading survivor statements as objective in view of the passage of time and the extraordinary trauma inflicted on survivors, but it is unwarranted to suggest that many compensation claims relating to medical experiment victims were illegitimate.

The vast majority of medical experiments conducted in Auschwitz and other concentration camps were scientific medical experiments, while at the same time inhumane, cruel and criminal. To categorize them as pseudo-medical experiments delegitimizes not only the suffering of the victims but the criminal medical process itself. To name just one example: Dr. Hans Hinselmann, the inventor of the colposcope, a technique that is credited with saving the lives of numerous women by detecting pre-cancerous growth in the cervix, used data from women incarcerated in Auschwitz’s Block 10 to improve his method.

The array of types of medical experiments carried out in foremost concentration camps is similarly important to note. While qualified research has taken place in the last couple of years to study not only what kinds of experiments were carried out, ranging from infectious disease experiments to sterilization procedures, research has also focused on how many victims were subjected to these procedures. This research is far from complete. A review of the Medical Experiments database maintained by the Claims Conference, which holds information provided by victims who filed an application form to the Fund for Victims of Medical Experiments and Other Injuries (which was part of the German Slave Labor Fund), revealed that a significant percentage of applicants are thus far not listed among other listings of medical experiment victims. In addition, through the processing of these claims, more types of medical experiments were revealed than initially known, in particular by the early compensation programs that were carried out in the 1960s and 1970s through the International Red Cross.

Ruth J. Weinberger

Historian

former assistant director, Fund for Victims of Medical Experiments and Other Injuries

Claims Conference

Borbála Klacsmann

Dear Ms Weinberger,

Thank you for the comment. I agree with your argument that several of the experiments were actually scientific, nevertheless, the terms “pseudo-medical” or “pseudo-scientific” is often used in relevant literature or websites (see for instance the description of the sources I used in this post at USHMM’s website: https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn47046). Also, I do not think that this term delegitimizes the suffering of the victims as I did not question that the experiments were conducted per se, or that they were cruel and the subjects were human beings. Rather, the term refers to the validity of the scientific results or the nature of the experiments, in my view. Nevertheless, I will pay particular attention to how I use it in the future.

As for the compensation claims, according to my research, it did happen quite a few times that someone who had not been experimented on, handed in a claim – at least in Hungary. I found at least three cases among 42 claims from Pest County. Another question is, whether or not these survivors received compensation later. In the Pest County cases I investigated, only the two women mentioned in the post received a sum from NÜÉSZ (which means that their applications were not sent to Switzerland; they got this sum because they were Holocaust survivors and not because they were experimented on).

In 1971, NÜÉSZ compiled a statistic in order to wrap up the compensation program of victims of medical experiments. According to this list, 1047 Hungarian survivors applied, out of them 45 applications were supported by the committee. 340 claims were formally correct; 257 cases were formally correct but the harmed health of the claimant “could not be proved” or the claimant him/herself did not label the intervention as a medical experiment. In 405 cases the application could not be processed either because the claimant had passed away in the meanwhile, s/he emigrated or it could not be proved that an experiment really took place. So based on these statistics, only a small amount of compensation claims were 1. formally correct 2. supported by convincing medical and other certificates 3. supported by the committee itself.

So basically the summary is that a) yes, quite a few people who had not been experimented on, handed in compensation claims, b) occasionally the committee supported cases where the claimant could prove the health damage, nevertheless in reality s/he had not been subjected to an experiment, i.e. the case was “illegitimate” (had it not been for Mrs. F. in the case above, Mrs. S.’s claim would have been sent to Geneva!), c) even so, the committee filtered out several illegitimate claims. Still, for me, the most important “message” here was that every survivor deserved a compensation – whether or not they were experimented on.