Edith Bruck

Edith Bruck is often called “Signora Auschwitz” in the press: her book with the same title was published in 1999.1 Only recently, with the English translation of her autobiography, she has received international recognition on a level commensurate with other writers of the Shoah like Elie Wiesel, Imre Kertész, and Primo Levi – just to list a few of those who are by now part of the Holocaust literary canon. The fast-growing literature on her focuses on issues of Jewish women writers and her choice of language, Italian, her husband’s native language, rather than her native Hungarian. In this literature, analysis of Bruck’s work as a poet and translator contributes to the study of theories of translation.

This post investigates a different, previously neglected aspect of her life and work, namely the role her works and testimonies played in constructing a memory of the Holocaust in her own native village, Tiszakarád, with an emphasis on the complexities of Jewish-Hungarian relations after the Holocaust.

Edith Bruck was born in Hungary in 1932. Before the Shoah, Edith Bruck lived in Tiszakarád in rural north-eastern Hungary. The village in 1941 had 4694 inhabitants including roughly a dozen orthodox Jewish families, altogether 94 people, who worked in agriculture, as butchers, in commerce, or as shop owners and managers. The community did not have a rabbi but observed all the holidays with services held in the local synagogue led by elderly members of the community who studied in yeshivas. The Jewish community was divided along economic lines. Edith Bruck’s parents were very poor. Her father was a traveling merchant known for making bad deals, while her mother was a homemaker. Other community members were prosperous enough to finance secondary and even higher education for their children.

Sources

This community is destroyed by today. The survivors left the latest by 1956 to Israel and the US. Five Jewish survivors of the deportations from Tiszakarád (Erzsébet Grosz, Adel Taub, Biri Goldstein, Ignác Grosz, Irma Nemény) were interviewed for the Shoah Visual History Archive (VHA) in the late 1990s.2

Please follow the link for the EHRI collection description :

The Hungarian documentary film, The Visit (1983), records Bruck’s return to her village in communist Hungary with a Hungarian film crew. Bruck sought to define herself as a ‘moral witness’ in the process of making this film.

In addition, I also conducted two interviews with Bruck in her home in Rome in 2002.3

The first visit

Bruck’s first visit to Tiszakarád after her deportation happened right after the war in 1945 and was short-lived. After being liberated from the Auschwitz concentration camp, she returned thin as a skeleton to her home village to locate surviving family members. Such quests were hardly unique: two other Tiszakarád survivors recounted similar stories of their return in their oral histories. Ignác Grosz, for instance, lived in the house of a non-Jewish villager in Tiszakarád until he married upon his return, and later left Hungary for Israel. Irma Nemény warmly recalled her return and finding several individuals who had worked for her father, the rich agricultural entrepreneur. During the first visit to Tiszakarád, Edith Bruck recounted how she was harassed by the village inhabitants who had not expected her to return at all. This is in line with post-war, post-Shoah antisemitism which resulted in a series of pogroms across Hungary.4

Like other survivors, Bruck did not wait to experience more violence and moved to Slovakia, she later immigrated to Israel.

She spoke about this decision in an interview:

“I went back to Hungary, to my village right after the war, and almost all the neighbors were driven away. They [villagers. A.P] were afraid that we would take back their poor things, we would punish them for what they did because there was Communism and the accusation was that the Jews brought Communism there.”5

However, another story emerges from her sister Adel’s account:

“[…] went to the house and collected what I could. The stove was taken away, I brought it back. The wardrobe. [She brought back the wardrobe. A. P.] Somebody lived in the house but left. I cleaned the house and we lived with my sister [Edith Bruck. A.P.]. My sister did not want to stay in [Tiszakarád. A.P.], so she left for my elder sister to Debrecen […] my [return. A.P.] was nothing special. The neighbors were happy or at least they pretended that they were happy. One of them said that this was taken away by that person that was taken away by somebody else. As I said I got back the stove, the wardrobe, and some other items. Whatever I could not, that I could not recover.”

The youtube video clip from the Interview of Adel Taub is from the collection of the USC Shoah Foundation – The Institute for Visual History and Education. For more information: http://sfi.usc.edu/

Other survivors who lived outside of Hungary when they were interviewed by the Shoah Visual History Archive, also only spoke about the tedious and painful process of recovering their own property from the villagers (VHA Erzsébet Grosz and Ignác Grosz) during the post-war period. The survivors, like Adel Taub, were not convinced by the authenticity of the joy villagers expressed upon the return of the Jewish population, but they tried to start a new life in the village, possibly again in their own homes.

The second visit

Bruck’s second visit happened in 1962 when she returned to the village together with her Italian husband. According to her testimony, she was harassed by the villagers and asked for money as they now recognized her as a rich foreigner. In the movie, The Visit6, recorded in 1982, she described this visit with horror and referring to it as her ‘first’ visit to Tiszakarád after her deportation. She probably did this in order to omit from her memory the more painful initial visit in 1945. The first visit of Edith Bruck to her home village happened when she was just one of the several ‘moral witnesses’, and before she became famous. In the film, she describes how in 1962, the village women surrounded her and demanded that she pay her father’s debts. “That was the last big slap in my face” – she said in the film about how her family was remembered by their neighbors even twenty years after (The Visit, transcript 22). The only source we have about what happened during this second visit is the interviews with Edith Bruck. As she constructed her fictional self-image with this film, whether this encounter really happened is not relevant as we have no way to check it.

The (second) Visit filmed

Bruck wanted to break the silence in Hungary about the deportation of Jews and the plunder of Jewish property with her 1982 film, and she based it on her own script. She was proud of the final result:

The film was a great success – produced by the state film industry. A film which called the Hungarians’ attention to themselves, to their own history and to their treatment of their Jewish citizens. In the schools then the students were taught that Hungary was allied with the Soviet Union during the Second World War and not with the Nazi fascists. The film for me was a terrible ordeal but it was my duty to make it, to uncover the truth of the facts and to reawaken drowsy or self-deluded consciences.7

The reception of the film was neither a success nor did it accomplish a coming to terms of Hungarians’ treatment of their Jewish neighbors. This was further complicated by the anti-fascist framework of remembering, which considered all victims of National Socialism as equal.8 When I interviewed Edith Bruck in Rome she again spoke of this film in relation to her self-representation as a ‘moral witness’:

“There is something that I bring to Hungary, and the whole country is watching the movie three times […] this happened the first with my movie. With the movie I made. The movie made about me. Through that movie it surfaced what happened in Hungary. Everybody was silent. […] They were silent in Hungary about what happened, because they [Hungarian Jews. A.P.] were a part of what happened, they were guilty. The Jews were as silent as the non-Jews.”9

Her uncertain formulation: “my movie. With the movie I made. The movie made about me“, highlights the political problems with the film and that is the topic of this post. Hungarian communist cultural norms in 1982 could not accept a film made about Hungarian rural antisemitism, collaboration, and plunder of Jewish property. Consequently, the Hungarian authorities used different strategies to prevent this from happening. Bruck who wanted to play the role of the ‘moral witness’ was vulnerable to these strategies and was easily manipulated. She was particularly vulnerable as she was alone in this process.

Making a Holocaust movie in communist Hungary in the 1980s was not an easy endeavor, especially not when the producer was an Italian citizen. Recently, the film’s director, László Révész (born 1942), gave two interviews about the politics impacting his production of The Visit. In one of them, he spoke of the constraints set by the Communist state authorities on the original script of the film by Bruck. “Then the Main Authority of Films ‘the omnipotent Main Directorate of Films’ (Filmfőigazgatóság) had a final word on each and every film made in communist Hungary” – said Révész and discovered that “the script by Edith is anti-Hungarian, shows the villagers as too racist even anti-Semites, therefore they do not support the making of the film”.10

After the original script of the film written by Bruck was rejected, the film making process was also sabotaged by pushing her to sign an unfavorable contract with the Hungarian Film Factory (Filmgyár). By now it is impossible to reconstruct the process as no paper trail is available in the archive. With this signature, Bruck commissioned all rights to actually produce the movie to the Hungarian Film Factory, a political move by the Hungarian state as it determined the movie would become part of communist cultural policy. It is understandable that she wanted to have her film made in and by the Hungarian state, the state which once sent her to Auschwitz. Révész, who had very good personal relations with this state institution, volunteered or rather jumped at the opportunity to make a documentary film about Bruck’s visit in Tiszakarád himself. He was considered politically reliable enough by the Communist authorities to make the controversial film. Révész’s decision was possibly not independent from the fact that the film was granted a lavish budget as representatives of official Hungary thought it would create a good public image of Hungary in the ‘West’ as far as the country’s participation in the Shoah was concerned. This filming budget included two state-financed trips to Rome for planning and filming at a time when state-sponsored business trips to the other side of the Iron Curtain were rare. The aim of the Communist authorities was to avoid a recording of an allegedly ‘anti-Hungarian’ film by all means. Révész himself came up with a compromise which gave the impression to Edith Bruck that she was somewhat in charge of the process of making the film but the final cut was made by the director under strict control of the authorities. Révész collaborated with the authorities to neutralize the film.

By then we were friends with Edith and it was my idea that with a twist we can make the film: a film about Edith Bruck, and in that somehow she can record that visit she originally planned to film in the original movie.11

Bruck signed the contract with the Hungarian Film Factory because she believed in what she was told. Namely that there would be two films produced in parallel: Bruck making the film of her own and Révész’s parallel film about Bruck making her own movie. This arrangement was aimed to calm Edith Bruck, and to avoid an international scandal, as Bruck by then was a well-known writer and artist in Italy. The Hungarian authorities wanted to avoid her using her press contacts to make public statements about how her film was being sabotaged.

By the end, only one film was made by Révész as he was commissioned as the only director by the Hungarian Film Factory. He had all the power not only to decide how many cameras were set up and where. It is clear that his editorial decisions were driven by political consideration: the communist cultural politicians were screening different versions of the film to different focus groups and adjusted the film according to the feedback they have received.12 Making the film was not an easy task, Révész still remembers how difficult it was for him when “as a director I had to say no” to Edith Bruck.13 From the afterlife of the story it is clear that Bruck was a tough negotiator and therefore the film did not become what it actually meant to be: a propaganda tool. However, with this movie made by the Hungarian state, Bruck lost control over ‘her’ film no matter that the film was expected to record her own life story. She spoke about her disappointment quite openly to me during an interview in 2002:

“They said they will make a movie about me and they commissioned it to László Révész. He did the movie but there were some problems. At the cutting they said the film was damaged by light that is the reason why that part is missing from the movie. I said I do not believe it. They wanted to keep something secret, there was censorship.”14

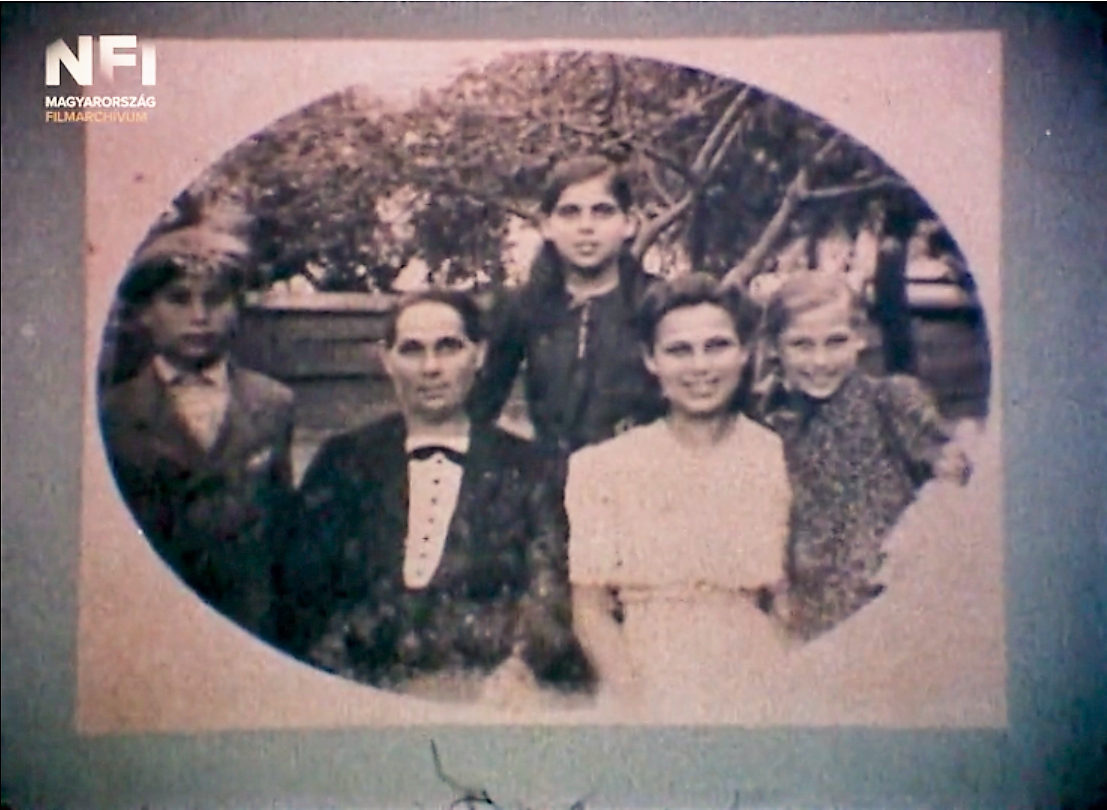

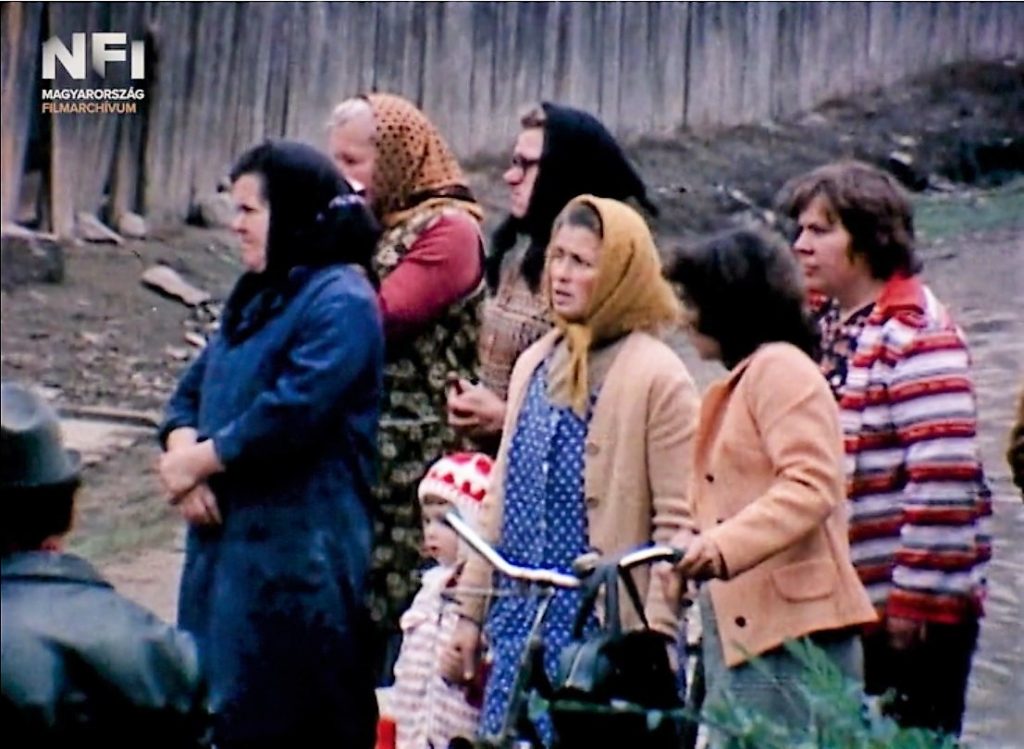

Stills from “The Visit”, Hungarian Filmarchive.

It is particularly difficult by now to reconstruct what parts of the film were deleted due to censorship. Based on the interviews, a number of problematic flash points emerged during the film making process, each one connected with the representation of the responsibility of non-Jewish Hungarians for the Shoah and the memory of the Shoah. First, the Jewish cemetery in Tiszakarád was totally neglected by the authorities, but it was renovated quickly before the arrival of the film crew. Second, Edith Bruck’s family home had been abandoned and ruined after the family left the village. The poor family of Edith Bruck moved into a new house in 1944 with hope and pride, as she describes it in her autobiography: Who loves you like this.15 The house was significant to Bruck’s sister, Adel Taub, who, in her Shoah interview, wanted to present a photo of the family home, but encountered apparent disinterest on the part of the interviewer, who favored a poster advertising The Visit focusing on Edith Bruck’s return to Tiszakarád. Since Edith Bruck photographed the house during her visit in 1962, the issue was even more complicated; the local authorities rightly assumed that she expected to see the same house again in 1982. At the end of each VHA interview the interviewees showed photos of their choice and therefore we know how important the house was to Adel Taub, the sister of Edith Bruck. The Communist authorities intervened by informing the villagers who owned the Brucks’ former home that they would demolish it after the film crew left Tiszakarád. In this way, the house was picturesquely filmed as a symbol of absence and destruction.

Next to filming its desolate condition, the movie used earlier photographs of the house to underscore its neglection.

The third critical point was a staged meeting with villagers, following tensions from previous visits as well as Bruck’s remarks about the inherent antisemitism of the villagers in her autobiography. Director Révész later explained that the villagers were informed about Bruck’s visit by authorities who shadowed the visit and that the villagers’ reactions were carefully choreographed. As the cameras rolled, the villagers, apparently spontaneously, prepared a meal to celebrate the return of the village daughter – Bruck.

In reality, it was planned while Bruck was taking a 300 km taxi ride from Budapest to Tiszakarád. On the day of filming, one camera was already set up in the main square to show the taxi slowly arriving in Tiszakarád.

Another camera recorded Edith Bruck, who wore a microphone. The script deliberately confuses past and present – as the taxi approaches the village, Edith Bruck enthusiastically and repeatedly exclaims on her own: “I know this, I live here” (The Visit, transcript 25).

She uses the present tense as if she had never left the place as a proof that her testimony is in making. This third visit to Tiszakarád serves as normalization of memory, or as the meta-visit while creating a presentable version of the Jewish-Hungarian relationship in Tiszakarád to the viewers of the documentary film.

The motion of the camera tellingly informs the viewers that the “spontaneous” interest of the village inhabitants was carefully planned, as well as their emotional outbursts. After the arrival of the film crew in the village, women gathered around Bruck, kissing her, their tears flowing as if a long lost daughter had arrived unexpectedly. The choreographed performance depicted how loved she was in the village and how happy her neighbors were to see her again, a powerful part of the film.https://blog.ehri-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Still11.png

The only sign that the relationship between Bruck and the villagers was not always idyllic is when an unidentifiable woman brings a worn tin pot to Edith and says: “That was sent to you by Aunt Vali, this was your pot, so please accept it with love.” (The Visit, transcript 41).

Accepting a worn tin pot stolen forty years earlier from the house of her murdered mother by a stranger with love would be a very difficult gesture in reality. Bruck bursts into tears as she looks and holds it. Here her return to her place of birth becomes a process of self-victimization. She weeps and sings Hungarian songs with the villagers, as she eats their food and accepts their hospitality as if she were being welcomed back into a fold from which outside forces – not the villagers – had expelled her.

According to psychoanalytical studies, having “transitional space” is essential to ever recover from trauma16. The film The Visit likely provided Edith Bruck a space for recovery and a space of ‘moral witnessing’.

The movie is obviously staged by the Communist authorities as a “movie about Bruck and her survival – not about Hungary during the Holocaust”17. From several hours of footage recorded in the village only 18 minutes made it into a 76-minute film after careful editing, test screenings and approval from different authorities needed to be screened in public. The Visit was also screened for the local village authorities prior to being released. They allegedly openly protested the film’s overemphasizing on the poverty of the village. This might led to the fact that only a fraction of the visit itself made it into the movie. What else has been cut we will never know. The rest of the film is filled with interviews of Hungarian intellectuals about Edith Bruck and interviews with Bruck herself.

Conclusions

Bruck’s ordeal did not end there. The film appeared on television, but then disappeared from public circulation. It received mixed reviews at the annual documentary film competition in Hungary. The chief jury member, influential Communist literary critic, István Király (1921-1989) criticized the film’s “baroque elements”. This was probably code for the overflow of emotions present in the film. Bruck’s only weapon was her international acknowledgement as an Italian writer which proved ineffective against the strong will of selective silencing by Communist cultural policy. She wanted to be a proud protagonist of a movie so she applied self-censorship for quite a while. Bruck first spoke about the film this way during the interview with me. Bruck’s effort to contribute to the process of remembrance brought very mixed results in generating a highly sanitized, feel-good narrative of deportation and survival of Jews from Tiszakarád, effectively repressing the trauma of her first return to her home village.

- Bruck, Edith (1999): Signora Auschwitz. Il dono della parola. Venezia. ↩

- Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive (VHA): Interviews with Testimonies Goldstein, Biri (19069), Grosz, Erzsébet (3792), Grosz, Ignác (3803), Nemény, Irma (4417), Taub, Adel (42036). ↩

- Pető A. In Transit: Space, People, Identities. Intermezzo. In: Passerini L, editor. Women migrants from East to West : gender, mobility and belonging in contemporary Europe. New York: Berghahn Books; 2007. p. 243-51. ↩

- Pető A. About the Narratives of a Blood Libel Case in Post Shoah Hungary. In: Vasvári L, Tötösy de Zepetnek S, editors. Comparative Central European Holocaust studies. West Lafayette Ind.: Purdue University Press; 2009. p. 240-53. ↩

- McGlinn, Marguerite (2002): Who Loves you Like This. A Holocaust Memoir by Edith Bruck. Curriculum Guide. Philadelphia, p. 35. https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0446/9005/files/bruck_guide.pdf (04.11.2018) ↩

- László B. Révész (dir.): A látogatás (The Visit), 1983, film. ↩

- McGlinn, Marguerite (2002): Who Loves you Like This. A Holocaust Memoir by Edith Bruck. Curriculum Guide. Philadelphia. https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0446/9005/files/bruck_guide.pdf (04.11.2018) ↩

- Pető, Andrea (2019): ‘Non-Remembering’ the Holocaust in Hungary and Poland. In: Guesnet, Francois/Lupovitch, Howard/ Polonsky, Antony (eds.): Polin. Polins Studies in Polish Jewry. Vol. 31. Poland and Hungary Jewish Realities Compared. Liverpool, 2019, 471-480. ↩

- Pető, Andrea (2002, 2nd of January): Personal interview with Edith Bruck, Rome, Italy. ↩

- Dunavölgyi, Péter (2013, 6th of March): Interview with Laszló B. Révész. In filmeshaz.hu. http://www.filmeshaz.hu/mtvtortenet/interjuk/int_B/int_BReveszLaszlo.htm (04.11.2018). ↩

- Szekfű, András (2015): László B. Révész: “A látogatás”. 100 magyar dokumentumfilm, emphasis A.P. In: Youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJ5CVunrQik (04.11.2018) ↩

- Szekfű, András (2015): László B. Révész: “A látogatás”. 100 magyar dokumentumfilm. In: Youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJ5CVunrQik (04.11.2018) ↩

- Szekfű, András (2015): László B. Révész: “A látogatás”. 100 magyar dokumentumfilm. In: Youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJ5CVunrQik (04.11.2018) ↩

- Pető, Andrea (2002, 2nd of January): Personal interview with Edith Bruck, Rome, Italy. ↩

- Bruck, Edith (2001): Who Loves You like This. Philadelphia. ↩

- Laub, Dori (1992): Bearing witness or the vicissitudes of listening. In: Felman, Shoshona/Laub, Dori (eds.): Crises of Witnessing in Literature, Psychoanalysis and History. New York, 57-74, p. 58. ↩

- Szekfű, András (2015): László B. Révész: “A látogatás”. 100 magyar dokumentumfilm. In: Youtube.com. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dJ5CVunrQik (04.11.2018) ↩

One Comment Leave a reply