“I give you my treasure. I beg you – you are also a mother – to save my child. God will repay you for everything, and I will too (…). My child will bring you luck, you will see. I beg you, yourself a mother, to have mercy on my child (…).”1

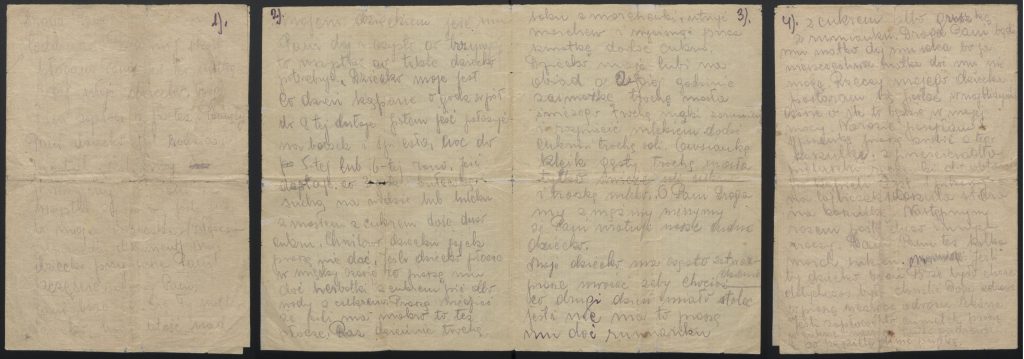

Thus begins a desperate plea of a Jewish mother, Eda Kunstler, to a Catholic mother, Zofia Sendler. Eda searched for a way to save her infant daughter Anita from the Kraków ghetto in German-occupied Poland. The letter written in 1943 testifies to the desperation that Eda faced and illuminates the shreds of agency that she strove to exercise as a mother. More broadly, Eda’s note demonstrates the impossible choices that parents were forced to make in an effort to try to assure their children’s survival during the Holocaust.

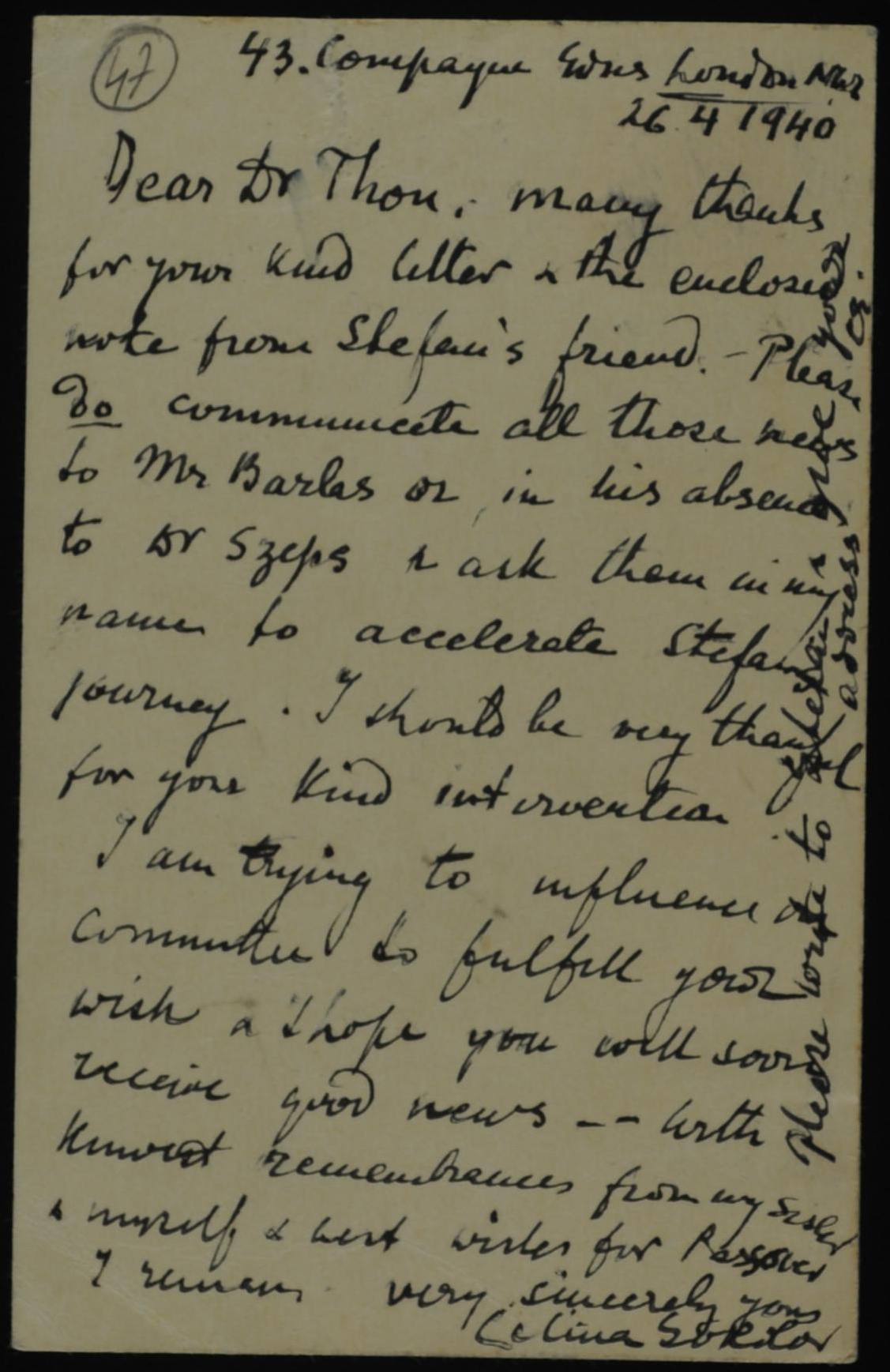

This letter is part of a small collection of documents and photographs that Anita Epstein (nèe Kunstler) donated to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in 2001. The collection has since been digitized and made available on the Museum’s website. The correspondence (written in Polish) and the accompanying photographs elucidate the history of one Jewish family during the Holocaust and depict the Jews’ efforts to rebuild their lives after the war, including the obstacles that Jews encountered, not least the recovery of their properties. It includes information on how wartime rescue was organized and reveals postwar relationships between rescuers and rescuees. The story that unfolds below analyzes the epistolary material and images from the USHMM collection in conjunction with other sources. Archival sources analyzed here highlight the importance of the continued efforts to acquire, digitize, and publicize Holocaust-related documentation. Brief and seemingly inconspicuous materials inspire new research questions and perspectives. In this case, they shed light on Jews’ choices during and after the war, and on Polish-Jewish relations.

On November 18, 1942, Eda gave birth to a baby daughter, Anita, in the Kraków ghetto. Just a few days earlier, on October 28, the German authorities had unleashed the second action in which they transported some 4,500 Jews to the Belzec death camp, and murdered about 600 Jews inside the ghetto. Anita’s parents, Eda and Salek, strove to save their daughter.

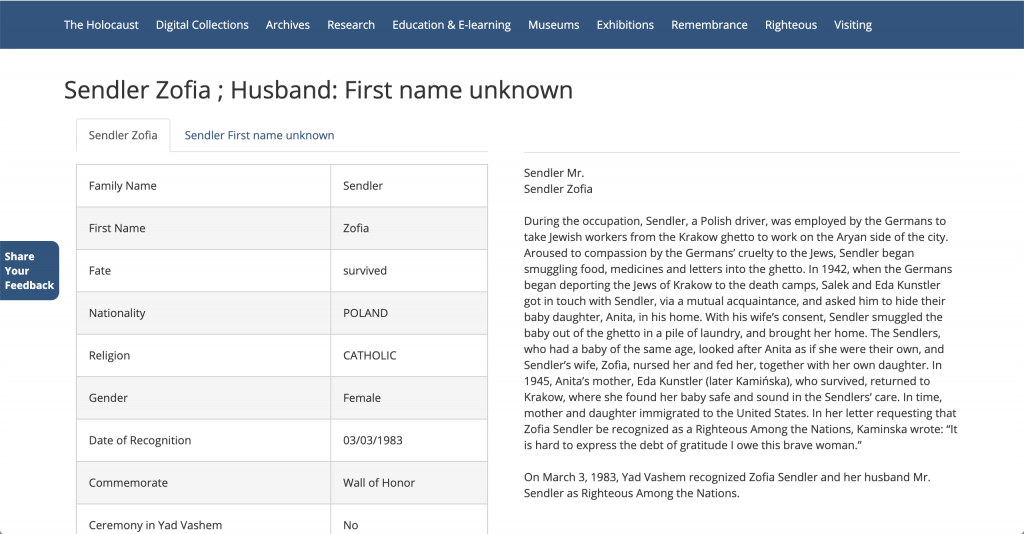

The Kunstlers established contact with an ethnic Pole, Mr. Sendler (his first name is unknown), through a mutual acquaintance. According to a summary that the Righteous Among the Nations Department at Yad Vashem published on its webpage, Sendler worked as a driver for the German authorities, taking Jewish workers from the ghetto to work on the Aryan side of the city.

He used his access to the ghetto to bring in food and medicine and deliver letters. Sendler, already a savvy participant in covert activities, hid Anita in a pile of laundry and smuggled her out of the ghetto.2 Eda’s version, however, differs. In an oral history recorded for the Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive in 1995, Eda explained that during the liquidation of the ghetto in March 1943, it was Salek, the girl’s father, who smuggled Anita out of the ghetto in a cab and brought her to Zofia Sendler (see Interview with Eda Kaminski below).3

It is unknown if, and to what extent, Zofia was involved in the decision-making or if she was simply faced with the outcome of arrangements that her husband had made with Salek. Regardless, Zofia protected, nursed, and raised Anita. This she did while caring for three of her own children, including a baby Anita’s age. The letter that opened this post illuminates the arguments that Jewish mothers used with potential caretakers to persuade them to save their children. Eda appealed to Zofia’s maternal instinct. She emphasized Zofia’s own role as a mother and hoped that Zofia would understand Eda’s desperation to save her child. Eda also referred to Zofia’s religion. A good Catholic, Eda implied, would not only shelter a Jewish baby but also care for the baby as her own. In fact, as Eda noted, the child would bring the Sendlers good fortune. Eda highlighted the ease of caring for Anita by pointing out that the only things the baby required was to be kept clean and to be fed. She praised her child, hoping that Zofia, too, would see Anita for the delightful and easygoing baby that Eda presented her to be. “Oh Dear Lady, my husband and I believe that you will save our marvelous child,” Eda implored Zofia.4

The letter served as an extension of parenting for Eda. Her detailed instructions urged Zofia to continue the care rituals that the baby used to receive from her biological mother. This information also served to ease the added responsibility of tending to a stranger’s baby. Eda specified what she had learned in the few short months during which she was able to care for her daughter. She hoped to assure the best possible care for her baby and, to the extent possible, a seamless adjustment for Zofia.

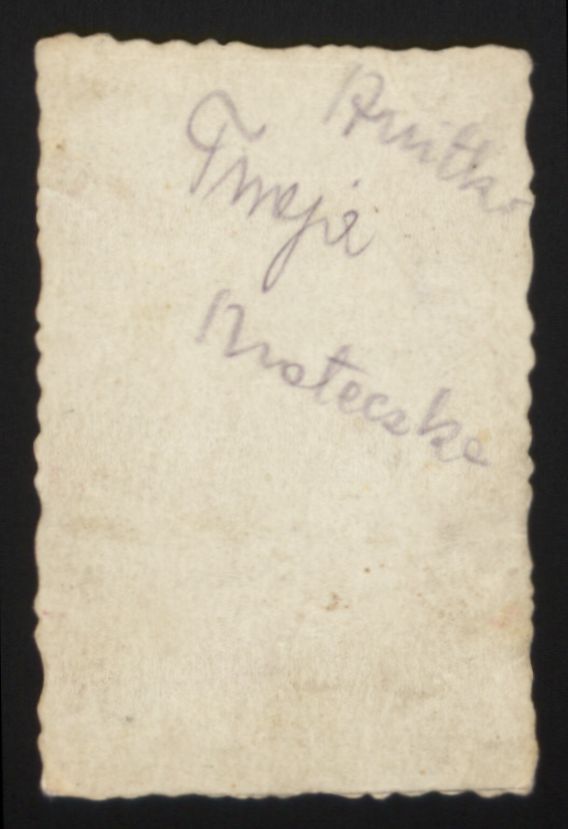

The meticulously outlined guidelines illuminate Eda’s tragic circumstances. She was not only denied the role that she now hoped Zofia would assume, but she also faced the unimaginable pain of forced separation from her baby daughter. Anticipating reuniting with Anita after the war, or at least wishing that her daughter knew her biological mother, Eda included a photograph of herself along with the letter. A message on the rear of the photo reads “Anitko [diminutive of Anita], your mommy.”5

Portriat of Eda Kunstler (left); back of the portrait of Eda Kunstler (right) with the note “Anitko” [diminutive of Anita], your mommy”. Anita Epstein papers, USHMM 2001.321.1.

Uncertainty of how her child would be treated by complete strangers combined with the concern about what would happen to Anita transpired in the letter. Eda appealed to Zofia, “Dear Madam, be a mother to her, give her your heart, because I, a hapless mother, cannot give that to her.”6

The Sendlers risked their lives by keeping Anita in their home. The German authorities instituted a death penalty on October 15, 1941, seven months after the creation of the ghetto. The law applied to any unauthorized Jew found outside the ghetto, to any gentile who knowingly provided shelter to Jews, as well as to helpers and abettors. An attempted gesture was treated the same as an accomplished act. The Sendlers faced a strict Nazi law and operated in an environment that was not conducive to helping Jews. In fact, Polish neighbors informed on the Sendlers. German officers barged into their apartment in search for the Jewish child. Zofia managed to deceive the oppressors with the girl’s false birth certificate, but she did not trust her neighbors and fled with the children to Kattowitz (Katowice) in German-annexed western Poland. It was there that Anita awaited liberation.

Anita while in hiding approx. 1943-1945 (left); Anita portrait while in hiding approx. 1943-1945 (right) – notice the necklace with the cross to evoke the Catholic background of the child. Anita Epstein papers, USHMM 2001.321.1.

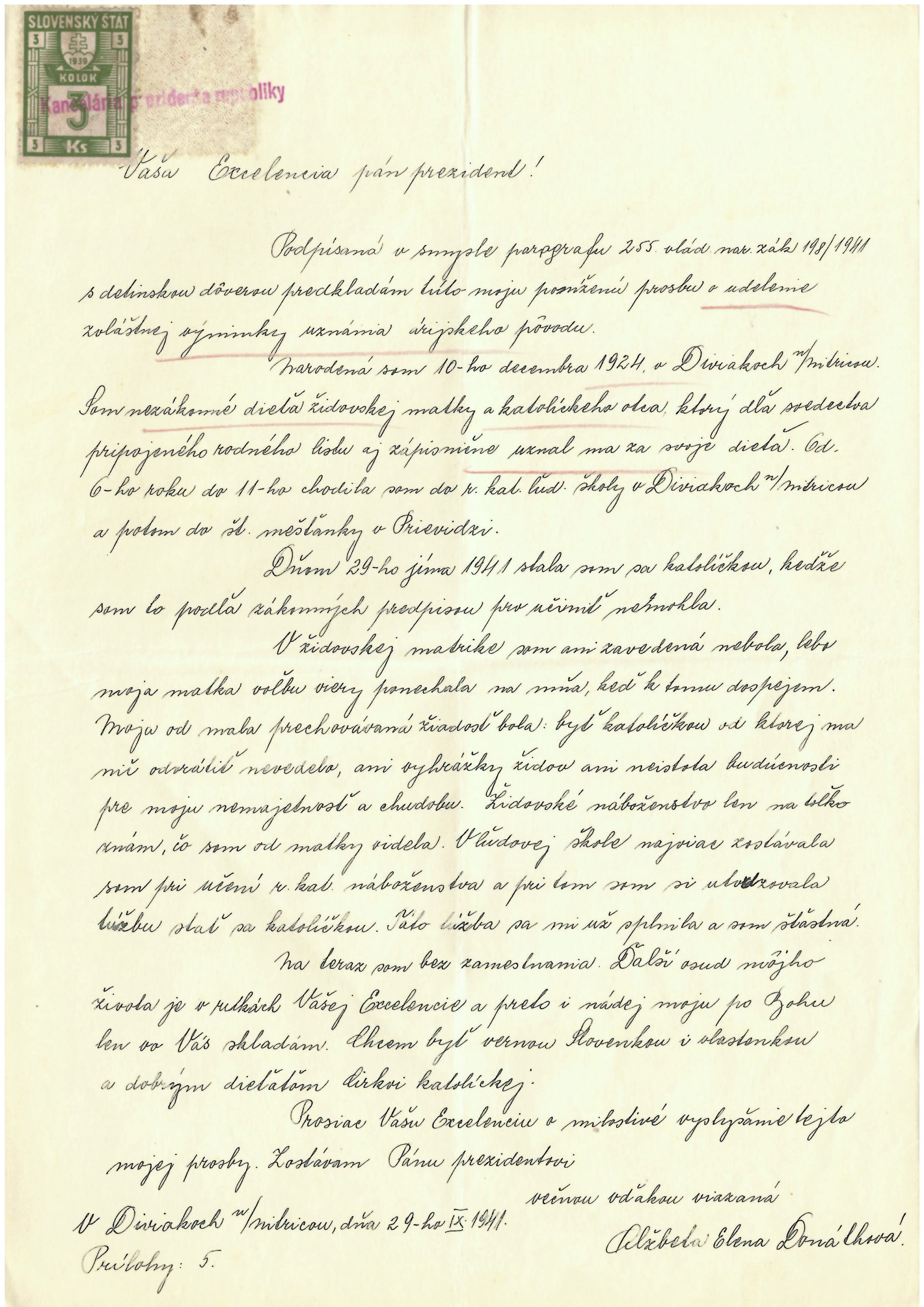

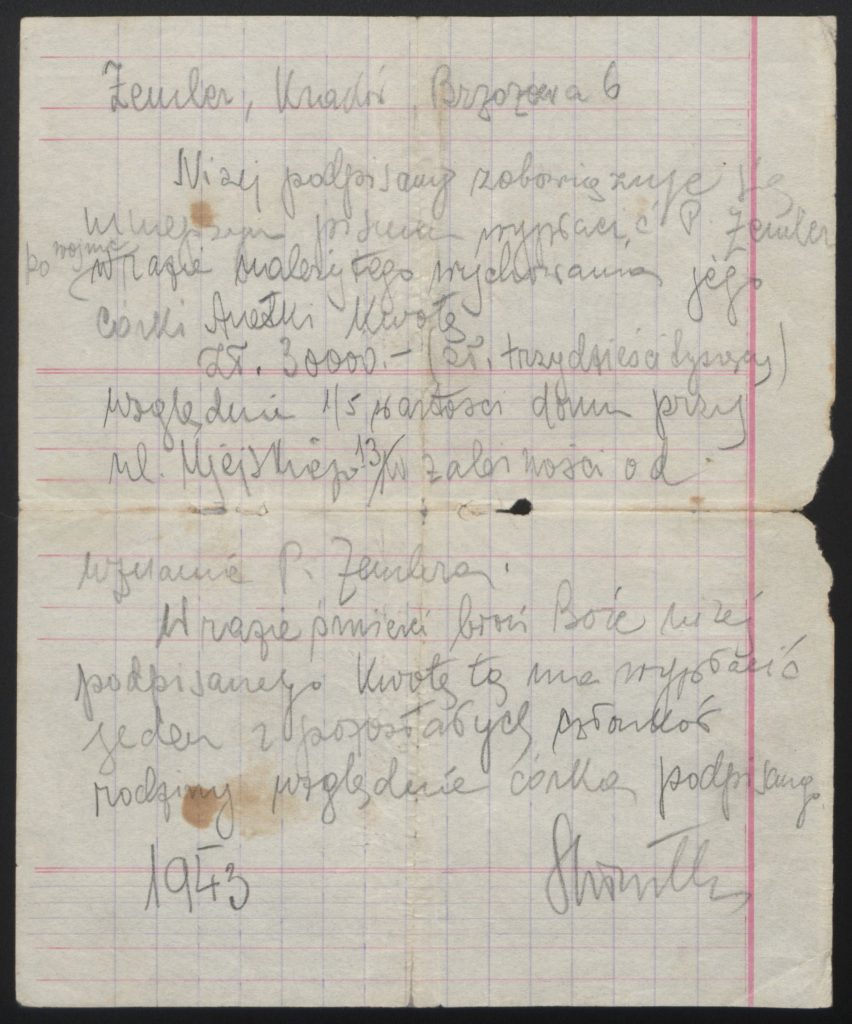

The Kunstlers were aware of the risks to which their child exposed the Sendler family. Thus, Eda wrote in her letter to Zofia, “If we survive we will pay you for everything, and if not, then my daughter will (I attach an appropriate document).”7 That document, signed by Anita’s father, promised to compensate the Sendlers (spelled Zendlers) 30,000 złoty or one fifth of the value of the Kunstlers’ house at 13 Ujejskiego Street in Kraków, based on Mr. Sendler’s preference.8

As Eda stated in her postwar account, “how long we could, we paid.” The Kunstlers’ acquaintance, a Jewish policeman, delivered to the Sendlers money and some other goods for Anita. The bulk payment mentioned in the letter would be issued after the war, which served as a guarantee that the Sendlers continued to shelter Anita. Fearing that he too may fall victim to Nazi genocidal policy, Salek designated any other surviving relative, or his daughter to fulfill the commitment. It is unknown if the Sendlers required such promise and if they expected remuneration for hiding Anita. Irrespective of that, Salek’s financial pledge served as both an exit and safety passport for Anita.

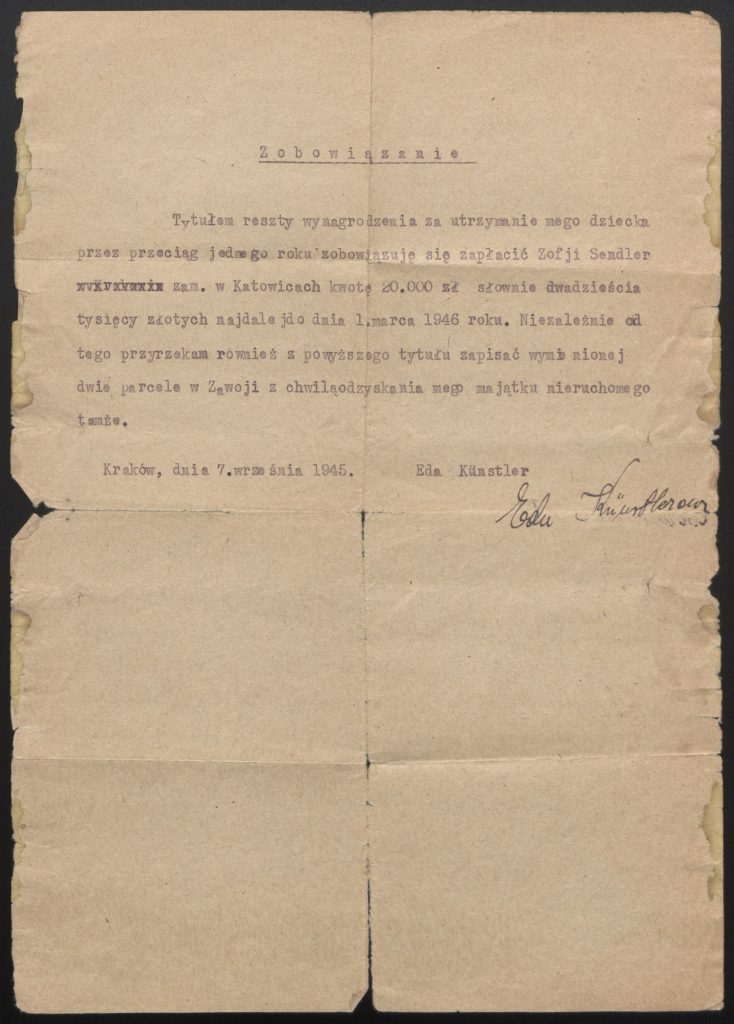

After the war, Eda reclaimed her daughter from the Sendlers. She also strove to fulfill her murdered husband’s vow. By September 7, 1945 when Eda wrote her letter, the Sendlers had already received 10,000 złoty as partial payment. Eda promised to pay the remaining 20,000 złoty to Zofia by March 1, 1946. She also obliged to transfer to Zofia ownership of two land parcels in her native Zawoja, a village in the mountains located about 40 miles away from Kraków, once Eda recovered them.9 Eda mentioned in her postwar account that her sister-in-law who lived in England sent money to pay Zofia (see interview with Eda Kaminski below). Eda explained, “Because this [Anita’s rescue] was for money. In the letter I’d say she [Zofia] would get a lot of money and she did.” However, as Anita admitted in her memoir, Zofia never received the promised real estate. Eda was unable to reclaim it, and as of 2012, neither was Anita. Still, both Eda and Anita offered a range of support to Zofia and her family.

In 1983, Yad Vashem bestowed upon Zofia Sendler and her husband the Righteous Among the Nations award. When asked by the interviewer from the Shoah Foundation why she thought that Zofia rescued Anita, Eda replied, “Because she was a good woman.” But Eda also understood that this was a hard decision to make and it involved sacrifices, and added that “for money, people would do a lot” at the time.

Correspondence, including that which the Kunstlers passed to their daughter’s protectors, offer a rare glimpse into rescue arrangements as the events unfolded and into the ways in which parents (in this case, a mother) grappled with separation from their children. It was not uncommon for Jewish parents to forward letters, such as those penned by the Kunstlers, to their children’s rescuers. At times, parents placed written messages with the child, or equipped the child with a small memento that would remind him or her of the family and of the child’s heritage in case the biological family did not survive. Letters and notes were not always preserved, mainly for safety reasons. The ones that were, such as those from the Kunstlers, render a raw account of the reality at the time and of the emotions that individuals felt and that motivated their choices. It is uncertain whether Zofia Sendler’s only reason for keeping the written messages was that they contained the terms of Anita’s rescue. What is significant is that the notes were retained and later returned to Anita’s family. By making them available to researchers, this epistolary and photographic material opens additional and new lines of inquiry.

- “Letters from Eda and Salek to the Zendler family, 1943.” Anita Epstein papers, USHMM 2001.321.1. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn512279#?rsc=130504&cv=1&xywh=-189%2C-1%2C3976%2C2605&c=0&m=0&s=0 ↩

- “Sendler, Mr., and Sendler, Zofia,” in The Encyclopedia of the Righteous Among the Nations: Rescuers of Jews during the Holocaust: Poland 2, ed. Israel Gutman, Sara Bender, and Shmuel Krakowski (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2004), 702; “Sendler Family,” Righteous Among the Nations, Yad Vashem, accessed May 24, 2019, http://db.yadvashem.org/righteous/family.html?language=en&itemId=4035266 and http://db.yadvashem.org/righteous/righteousName.html?language=en&itemId=4038010. The full file is not available to researchers. ↩

- This happened probably on March 13, 1943 when Jews whom the German authorities deemed able-bodied were transferred to the nearby Plaszow camp. Eda Kaminski, Interview 8985, USC Shoah Foundation Visual History Archive. November 19, 1995. Anita expanded on that story in her memoir. See Anita Epstein and Noel Epstein, Miracle Child: The Journey of a Young Holocaust Survivor (Boston, MA: Academic Studies Press, 2018), 32. ↩

- “Letters from Eda and Salek to the Zendler family, 1943.” Anita Epstein papers, USHMM 2001.321.1. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn512279#?rsc=130504&cv=1&xywh=1542%2C1095%2C2301%2C1507&c=0&m=0&s=0 ↩

- Photograph of Eda Kunstler. Anita Epstein papers, USHMM 2001.321.1. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn512279#?rsc=130511&cv=1&xywh=-347%2C-1%2C1257%2C824&c=0&m=0&s=0 and https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn512279#?rsc=130511&cv=2&xywh=-349%2C-1%2C1265%2C829&c=0&m=0&s=0. ↩

- “Letters from Eda and Salek to the Zendler family, 1943.” Anita Epstein papers, USHMM 2001.321.1. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn512279#?rsc=130504&cv=2&xywh=30%2C168%2C1930%2C1264&c=0&m=0&s=0 ↩

- “Letters from Eda and Salek to the Zendler family, 1943.” Anita Epstein papers, USHMM 2001.321.1. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn512279#?rsc=130504&cv=1&xywh=-189%2C-1%2C3976%2C2605&c=0&m=0&s=0 ↩

- “Promises of payment, 1943—1945,” Anita Epstein papers, USHMM 2001.321.1. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn512279#?rsc=130506&cv=0&xywh=-813%2C0%2C3570%2C2338&c=0&m=0&s=0 ↩

- “Promises of payment, 1943—1945,” Anita Epstein papers, USHMM 2001.321.1. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn512279#?rsc=130506&cv=1&xywh=218%2C694%2C2182%2C1429&c=0&m=0&s=0 ↩