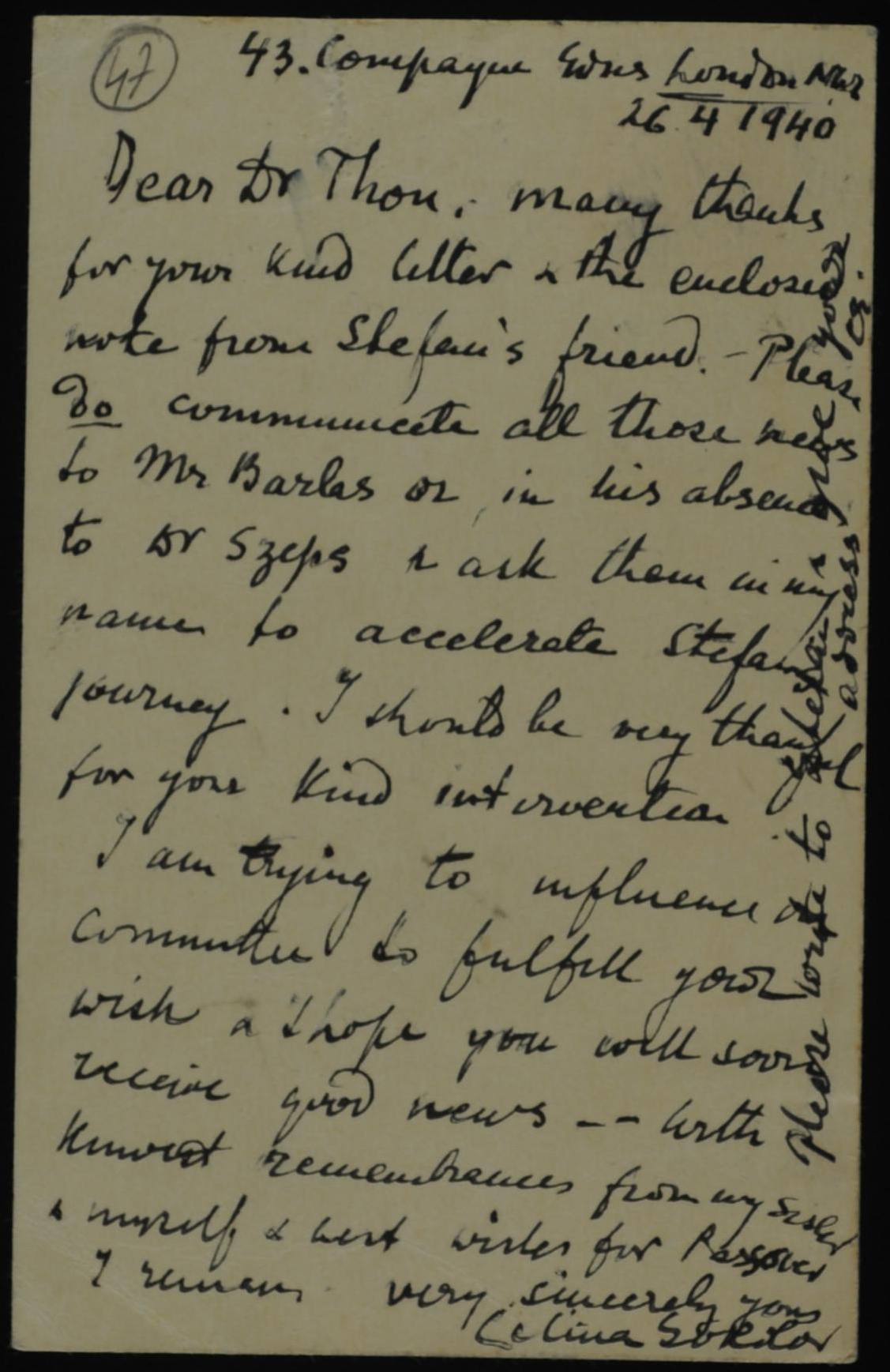

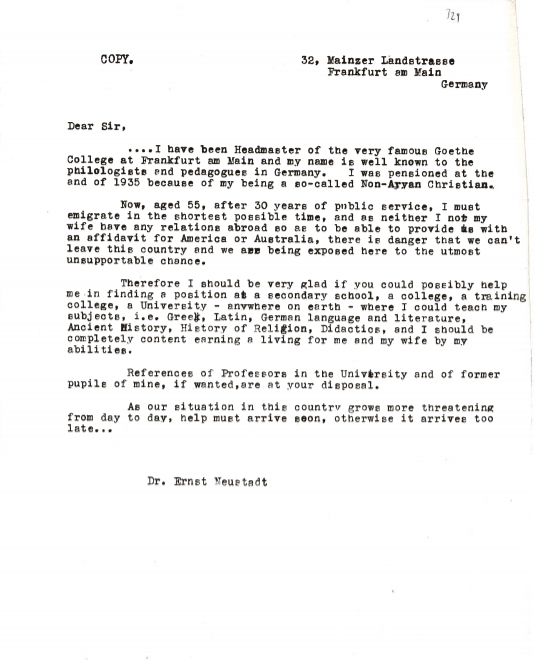

On 1st February 1946, Prof. J. B. Skemp, a Greek scholar and secretary of the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning (SPSL), an organisation designed to help academics at risk in occupied Europe, wrote a letter to Dr Ernst Neustadt addressed to 53 Belsize Park Gardens, London:

‘On going through our files, I noted that we had not heard from you for some considerable time. I am therefore writing to find out how you are and what work you were and are able to do. We should particularly like some sort of statement on the work you did during the war years […]’.1

Beyond Neustadt having last lived in Yorkshire, not London, he had sadly been dead for nearly four years after his suicide in April 1942. From 1938-41 the SPSL were unable/unwilling to help Neustadt, and only after the war, did Skemp reach out to him enquiring how he was. Through an analysis of Neustadt’s connections and correspondents, held by the SPSL Archive at the Bodleian, from early 1938 through to his eventual arrival in Britain in July 1939, the necessity of personal connections to migration can be highlighted alongside the emotions associated with emigration.

Scholars of German-Jewish refugees in the 1930s have often marginalised refugees into their own self-contained bubbles of analysis without identifying their connecting elements.2 Although some have noted the methodological and practical considerations of reconstructing the process of migration, it is evident that the historian can instead identify a range of connections between individual refugees and their friends, family, colleagues and supporters.3 As refugee studies continue to develop, and the divisions between the history of refugees and the history of the Holocaust begin to be identified and healed, the importance of microhistorical approaches to such areas is key to understand the nuanced and often specific nature of refugee dynamics.4 This post will predominantly use letters accessed through the SPSL archive, now known as CARA (Council for Assisting Refugee Academics), tracing Ernst Neustadt’s attempts to flee Nazi Germany.5 Recently Sally Crawford and others used the archives to discuss the activities and links of refugee scholars at Oxford University, indeed Harold Mytum in his chapter ‘Networks of Association’ paid credence to the myriad of connections many academics established.6 What is evident from Neustadt’s story, is that despite a wealth of connections, this was sometimes not enough.

Background: 1883 – 1938

Ernst Moritz Neustadt was born 21st March 1883 to David Neustadt (1838-1915) and Clara Joseph (1842-1919) in Charlottenburg, Berlin, less than a week after his elder sister Sophie (1879-83) passed away aged four.7 As a child, he enrolled at the Königliches Wilhelms-Gymnasium in Tiergarten, indeed his fellow classmate Kurt Hahn would go on to prove immensely helpful in procuring Neustadt’s escape. Neustadt went on to study at the Friedrich Wilhelm University (now called Humbolt University of Berlin) and eventually gained his PhD in 1906 under the tutelage of the philologists Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff and Hermann Diels.8 By 1909, Neustadt was working at the Mommsen Gymnasium and shortly began publishing articles and texts in both Latin and German such as Des Anaxagoras Lehre vom Geist in 1914 and Die religiös-philosophische Bewegung des Hellenismus und der Kaiserzeit the same year. In 1919, Ernst Neustadt married Gertrud Sara Stadthagen (1889-1942) daughter of Dr Max Stadthagen (1850-1926) and Clara Schneider (1866-1941).9

In 1929, Neustadt and his wife relocated to Frankfurt, taking up the role of headmaster at the famed Goethe-Gymnasium. In his opening speech to the school he spoke of the importance of humanism and quoted Nietzsche on the ‘physical and spiritual development to clear and self-assured humanity’ extolling the virtues of the ancient Greeks on his faculty. Less than six years after arriving at Goethe, in 1934 Neustadt was removed from his position and was forced to take up a lower paid job at the nearby Lessing-Gymnasium. By December 1935 however, Neustadt was forcibly pensioned under the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service, despite having won a vote of confidence from the staff two years earlier when his job was first threatened.10 Although Neustadt would receive a small state pension, this would most likely not have been enough to emigrate and although no source material exists to ascertain whether Ernst and Gertrud Neustadt wished to leave Germany as early as 1935, Hagit Lavsky has suggested that many who fled in 1938/9 began to search for ways out years earlier.11

Attempting to Flee: November 1938 – July 1939

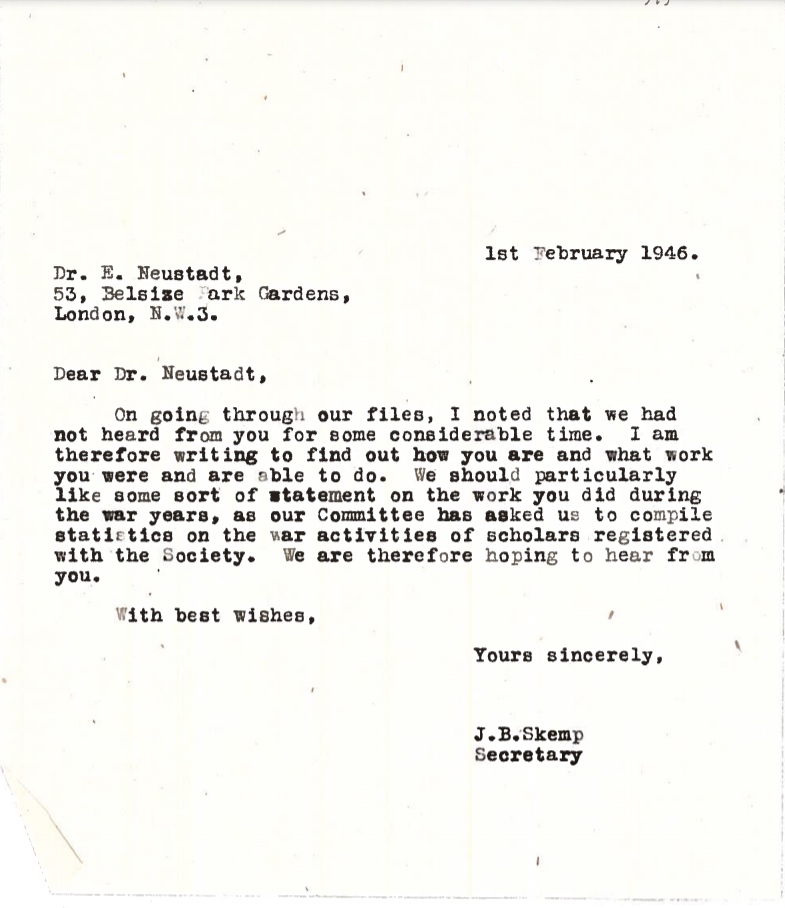

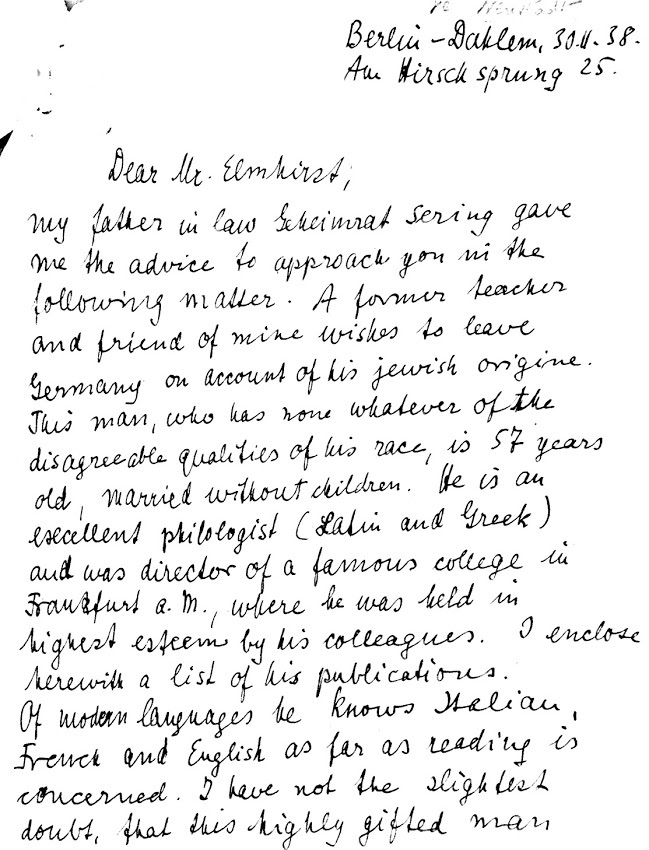

The advent of the November Pogroms in 1938 coincided with a mass increase in movement out of Nazi controlled Europe. While some historians argue increased emigration was a direct result of the pogroms, others suggest that it was instead the eased immigration controls in external states that precipitated increased migration.12 On 30th November 1938, a few weeks after the pogroms, Leonard Elmhirst, a noted agrarian from Devon, England, and the proprietor of Dartington Hall, a haven for exiled artists and performers, received a letter from Dr Wolfgang von Tirpitz regarding the fate of his friend Dr Ernst Neustadt.13 Asking Elmhirst to help Neustadt escape, Tirpitz wrote how he had ‘none of the disagreeable qualities of his race’ and was ‘after all a good Christian’.14 Leonard Elmhirst notes he knew Tirpitz’s wife, Elisabeth Sering, having worked with her father, Professor Max Sering, at the International Conference of Agricultural Economists where Elmhirst was President and Sering was Vice-President.15 In December that same year, having not heard from Elmhirst, Neustadt wrote a letter to Cosmo Gordon Lang, the Archbishop of Canterbury hoping to gain refuge on account of his Christian faith stating:

‘I nor my wife [Gertrud Stadthagen] have any relations abroad so as to be able to provide us with an affidavit for America or Australia, there is a danger that we can’t leave this country […] As our situation in this country grows more threatening from day to day, help must arrive soon, otherwise it arrives too late…’16

Although Ernst and Gertrud Neustadt had at least one cousin, Hanna Bergas (a teacher at the Bunce School for refugee children) in Britain by 1939, it is impossible to ascertain their relationship with her due to a lack of family correspondence.17 Along with his letter to the Archbishop, Neustadt included two references, one from a parent of a student, Lilly Lessing, who described him as a ‘progressive man of pure and clear character’, the other from the famed mathematician Professor Max Dehn who spoke highly of Neustadt’s academic achievements.18 Beyond his attempt at contacting the Archbishop of Canterbury, Neustadt sent the same letter to Gilbert Murray, Regius Professor of Greek at the University of Oxford, and his wife Mary, hoping their shared scholastic interests were enough to save him19 A subsequent letter was sent to Walter Adams in January 1939, whose address he had been given to Neustadt by Elmhirst, with the additional line ‘If it is not possible to get me a position immediately, I need most urgently an invitation to England in order to wait in security and without daily humiliation for the result of my further endeavours’.20 He was desperate.

In the months after the November pogroms, Neustadt had begun to utilise his connections within his academic circle, contacting friends of relatives of friends, highlighting the extent to which a myriad of connections became vital. In his application to the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning, who had repeatedly turned him down as he did not ‘count as an academic’, only a school teacher, Neustadt listed several famous colleagues and friends in his references including Eduard Norden, Eduard Fraenkel and Fritz Heinemann.21 Clearly, Neustadt was attempting to utilise his academic circle as he had no family abroad, although the inability/unwillingness of the SPSL began to cause problems, they did pass his enquiry to Dr Fritz Demuth of the Notgemeinschaft Deutscher Wissenschaftler im Ausland, this was also however, unsuccessful.22 Although Leonard Elmhirst had tried to facilitate Neustadt’s escape by contacting his friend Sir Henry Bunbury as both were members of the policy think-tank Political and Economic Planning (PEP), this was equally unsuccessful as both had filled their so-called ‘refugee quota’ by the beginning of 1939. From January to July 1939 we lose record of Neustadt’s attempts to emigrate and learn that despite Neustadt’s various attempts to flee Germany, his eventual escape was supported by Kurt Hahn, his childhood friend, who appealed to the Home Office for a visa to work at Gordonstoun School in Scotland. The correspondence of Kurt Hahn, held at Gordonstoun, could in theory be used to ascertain when Neustadt contacted Hahn, although many of these letters no longer exist. Neustadt’s successes and failures in his attempts to emigrate revolved around his relationships with colleagues and associates and their willingness, or ability, to help, and highlight the role of connections in facilitating escape.

What happened to Ernst and Gertrud Neustadt and where does the research go next?

Neustadt eventually made it to England, working at Gordonstoun School in Scotland under Hahn. He was subsequently interned on the Isle of Man but was released under Category 18, ‘Extreme hardship’, granted presumably due to his wife’s cancer diagnosis.23 Released from internment, Ernst and Gertrud Neustadt fell on hard times and moved to Wakefield in search of work after Gordonstoun School moved to Wales in the intervening period. Prior to this, Ernst Neustadt had been sending money via the Red Cross to his mother-in-law in Berlin, but with no finances himself Clara died destitute in October 1941 as the deportations from the city began. After the death of his wife in March 1942 and the redundancy from his new teaching position at Wakefield Grammar School, Ernst Neustadt committed suicide on 25th April 1942 with no family, no job and no money, a far cry from his previous life as a respected Classical academic.

Whilst this post examines the correspondence held mainly in the SPSL Archive at the Bodleian and covers a relatively small period, piecing together Neustadt’s life is a mammoth effort as he left behind no archive of letters, no family testimony and no physical trace to speak of. Whilst Ernst Neustadt was too ordinary to be considered appropriate by the SPSL, he was equally more well connected than many other refugees who wished to emigrate, often through family members or domestic service visas. The process of tracing anyone through archives is a challenge, let alone someone who led a relatively normal life – and yet these are the individuals most likely to tell us how the majority of people managed to emigrate. The SPSL archive linked Neustadt to a plethora of different individuals both in Germany and Britain at the time of his emigration and thus the next natural step would be to establish any reference to Neustadt in the collections of these individuals. For example the Kurt Hahn archive at Gordonstoun School in Elgin, the records of Notgemeinschaft deutscher Wissenschaftler im Ausland also held in the SPSL archive, and the papers of Gilbert Murray, could all provide extra information on how Neustadt managed to escape: who helped, who didn’t and who was unable to.

As for the United Kingdom, the Wiener Library has already begun with an interactive refugee map in the last few years, marking both the advent of public facing digitised access to refugee stories as well as a better understanding of the geographical spread of refugee diaspora ‘homelands’. In recent years a number of refugee narratives are being retraced in works by Esther Saraga, Joachim Schloer, and Shirli Gilbert, mainly through bequeathed masses of family letters.24 The process of recreating Ernst and Gertrud Neustadt’s story is however different as it has no base in a singular collection or archive, and is instead the result of piecing together various aspects of a story. As the refugee is transnational, so is the research; and perhaps as the editors and authors of Three-Way Street have argued, instead of mapping the refugee story as a linear chronology it is more helpful to present it as a ‘constellation of ties’, linked together across the spatial and temporal plains.25 One could in turn visualise Ernst Neustadt’s journey and others like him through their links to others and the places they inhabited rather than through the timeline of their life, at reduced risk of turning them into a list of dates.

Retracing Neustadt’s life through archives is an arduous task and one could legitimately ask ‘What is the point beyond historical intrigue?’. As far as I am aware Neustadt has no immediate descendents or family, and left no physical trace after 1942 beyond the sale of his furniture and effects in October 1944 – he doesn’t even possess a headstone.26 Although as a result of the initial research done on the Neustadt’s their Stolpersteine were laid in October 2020 outside Goethe Gymnasium where he worked in the 1930s and research into his connections and family continue. Neustadt’s story of emigration from Germany and his eventual demise in England demonstrate the many different avenues refugees explored when seeking to leave occupied Europe. This blog post has highlighted the series of letters within the period of a few months and how individual connections were key for fairly connected potential-refugees to escape. To move forward with the Neustadt’s story, a better visualisation of the connections will be needed to fully highlight both how the historian can trace individuals through a growing digitised archival space, and how important these personal connections were for refugees during the 1930s.

Note: Sections of this article are taken from the author’s MA thesis: ‘Jewish Refugees and the Concern for Those Left Behind: A Transnational History’ (University of Exeter, 2020). A map based visualisations of the life of Ernst Neustadt via ArcGIS StoryMap can be found here.

- Letter from J. B. Skemp to Ernst Neustadt, 1st February 1946, MS. SPSL. 295/6/366. ↩

- This division has been identified by scholars such as Deborah Dwork. See Debórah Dwork, ‘Refugee Jews and the Holocaust: Luck, Fortuitous Circumstances and Timing’ in “Wer bleibt, opfert seine Jahre, vielleicht sein Leben” Deutsche Juden 1938-1941 ed. by Susanne Heim, Beate Meyer and Francis R. Nicosia (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2010), pp.281-98 (p.281). ↩

- For a brief analysis of the importance of refugee studies and their historiography see Dan Stone ‘Refugees Then and Now: Memory, History and Politics in the Long Twentieth Century: An Introduction’, Patterns of Prejudice, 52/2-3 (2018), 101-106. See Gadi Benezer and Roger Zetter, ‘Searching for directions: conceptual and methodological challenges in researching refugee journeys’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 28/3 (2014), 297–318. ↩

- Scholars such as Joachim Schlör, have highlighted how macrohistorical approaches to refugees have been done, see his chapter ‘“Irgendwo auf der Welt”: The Emigration of Jews from Nazi Germany as a Transnational Experience’, in Three-Way Street: Jews, Germans, and the Transnational, ed. by Jay Howard Geller and Leslie Morris (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016), pp.220-38. ↩

- All material from the SPSL archive reproduced by kind permission of CARA (the Council for At-Risk Academics). See https://www.cara.ngo/. ↩

- See Harold Mytum, ‘The Social and Intellectual Lives of Academics in Manx Internment Camps during World War II’, in Ark of Civilization: Refugee Scholars and Oxford University, 1930-1945, ed. by S. Crawford, K. Ulmschneider, J.Elsner (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), pp. 96-116. ↩

- For more biographical information on Ernst Neustadt see Charlie Knight, ‘Dr Ernst Neustadt: Researching a Stolperstein’, The British Association for Holocaust Studies Blog (20th June 2020), Accessed via: https://britishassociationforholocauststudies.wordpress.com/2020/06/20/dr-ernst-neustadt-researching-a-stolperstein/, Last accessed: 1st December 2020. A full family tree of Ernst Neustadt and his wife Gertrud Stadthagen can be viewed at www.ancestry.co.uk/ ↩

- Ernst M. Neustadt, De Jove Cretico (Berlin: Mayer & Müller, 1906). ↩

- Biographical information of Neustadt can also be found in Rudolf Bonnet, Das Lessing-Gymnasium zu Frankfurt am Main: Lehrer und Schüler 1897 – 1947 (Frankfurt A.M: Kramer, 1954). Bonnet was a former student of Neustadt’s and a Nazi supporter during and after the war. ↩

- Note informing Neustadt of his Retirement, December 1935, Stadtarchiv, Institut für Stadtgeschichte Frankfurt, ISG 207.038; Neustadt Curiculum Vitae, MS. SPSL. 295/6/332-3. ↩

- Hagit Lavsky, ‘The Impact of 1939 on German-Jewish Emigration and Adaptation in Palestine, Britain and the USA’, in “Wer bleibt, opfert seine Jahre, vielleicht sein Leben” Deutsche Juden 1938-1941 ed. by Susanne Heim, Beate Meyer and Francis R. Nicosia (Göttingen: Wallstein Verlag, 2010), pp.207-25. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- See Michael Young, The Elmhirsts of Dartington: The Creation of a Utopian Community (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1982). ↩

- Letter from Wolfgang von Tirpitz to Leonard K. Elmhirst, 30th November 1938, DHC T/AA/1/J/7. Wolfgang von Tirpitz was the son of Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz although it is unclear how Tirpitz and Neustadt knew each other. ↩

- Letter from Leonard K. Elmhirst to Sir Henry Bunbury, 9th February 1939, DHC LKE/PEP/1/A/1. See Bernard F. Stanton, Agricultural Economics at Cornell: A History, 1900-1990 (New York: Cornell University, 2001), p.85. ↩

- Letter from Ernst Neustadt (to the Archbishop of Canterbury, November 1938), MS. SPSL. 295/6/329. ↩

- Gertrud Neustadt and Hanna Berger (1900-1987) were related through their mothers, who were sisters. Another of Gertrud Neustadt’s cousins, Fritz Phillipsborn (1888-1963) eventually relocated to London although it is unclear when this occurred. On Ernst Neustadt’s side of the family, his cousin Rudolf Bergstein (1888-1938) was killed during the November pogroms in Berlin and his wife Käthe (1887-?) moved to London, working as a Domestic Servant. ↩

- Letter from Lilly Lessing, 2nd December 1938, MS. SPSL. 295/6/335; Letter from Prof. Max Dehn, 12th December 1938, MS. SPSL. 295/6/330. Max Dehn also fled Nazi Germany in January 1939, for details of his escape see John W. Dawson Jr, ‘Max Dehn, Kurt Gödel, and the trans-Siberian escape route’, Notices of the AMS, 49/9 (2002), 1068-75. The papers of Max Dehn can be viewed at the Briscoe Centre for American History, see https://legacy.lib.utexas.edu/taro/utcah/00192/cah-00192.html. ↩

- Gilbert and Mary Murray became instrumental in the assistance of academics fleeing Nazi Germany. See various chapters in Christopher Stray (ed.), Gilbert Murray Reassessed: Hellenism, Theatre, and International Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007). Letter from Mary Murray to Mary Ormerod, 29th December 1938, MS. SPSL. 295/6/349. ↩

- Walter Adams was secretary to the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning when it was known as the Academic Assistance Council. See Sue Donnely, ‘Sir Walter Adams – School Secretary and Director’, LSE History Blog, 18th April 2018, Accessed via: https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/lsehistory/2018/04/18/sir-walter-adams-school-secretary-and-director/, Last accessed: 23rd July 2020. Letter from Ernst Neustadt to Walter Adams, 1st January 1939, MS. SPSL. 295/6/352. ↩

- For more on the SPSL archive see N. J. Baldwin, ‘The Archive of the Society for the Protection of Science and Learning’, History of Science, 27/1 (1989), 103-105; for its effect on the field see David Zimmerman, ‘The Society for the Protection of Science and Learning and the Politicization of British Science in the 1930s’, Minerva, 44/1 (2006), 25-45. ↩

- Letter from Esther Simpson to Fritz Demuth, 22nd December 1938, MS. SPSL. 295/6/347. For more on Notgemeinschaft Deutscher Wissenschaftler im Ausland see Roman Pauli, Jania Sziranyi and Dominik Gross, ‘Vom NS-Opfer zum Initiator der “Notgemeinschaft deutscher Wissenschaftler im Ausland”. Der Pathologe Philipp Schwartz (1894 – 1977)’, Der Pathologe, 40 (2019), 548–558. ↩

- See Rachel Pistol, ‘Routes out of internment – a handy reference guide to White Paper categories’, Dr Rachel Pistol Blog, 11th June 2020, Accessed via: https://www.rachelpistol.com/post/routes-out-of-internment-a-handy-reference-guide, Last accessed: 2nd December 2020. ↩

- Esther Saraga, Berlin to London: An Emotional History of Two Refugees (London: Valentine Mitchell, 2019); Shirli Gilbert, From Things Lost: Forgotten Letters and the Legacy of the Holocaust (Michigan: Wayne State University Press, 2017); Joachim Schloer, Escaping Nazi Germany: One Woman’s Emigration from Heilbronn to England (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2020). ↩

- Jay Howard Geller and Leslie Morris, ‘Introduction’, in Three-Way Street: Jews Germans and the Transnational, ed. by Jay Howard Geller and Leslie Morris (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2016), pp.1-19 (p.1). ↩

- Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 30th September 1944, p.3. ↩