Almost half of the Jewish population of Belgium was murdered during the Holocaust. Complete families were wiped out, creating blind spots in the information available to reconstruct their stories in particular, but also certain aspects of the Belgian case in general. Personal documents of survivors and non-survivors thus become even more important to fill these gaps in our knowledge. One such precious item is the clandestine diary of Mozes Sand. Between June 13 and September 12, 1942 over 2.250 Jewish men were deported from Belgium to Northern France as forced labourers for Organisation Todt (OT). Mozes was one of them. In his diary he describes many details that can hardly be found in other sources: the journey of the men, their living and working conditions at the campsites, the ways in which they could communicate with their loved ones who stayed behind in Belgium…

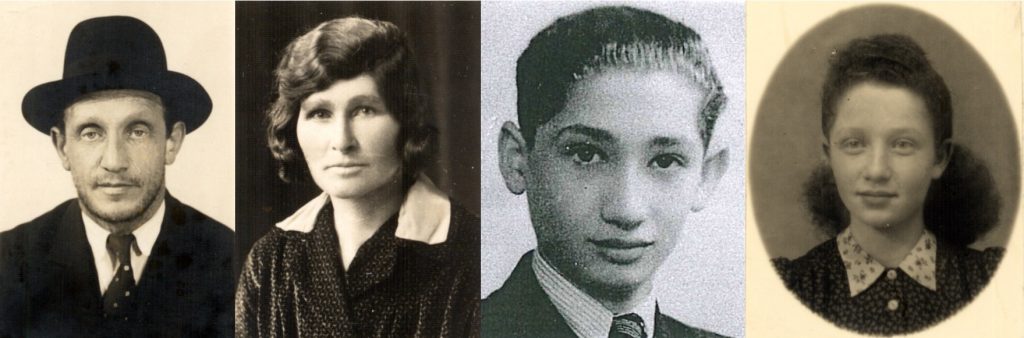

The importance of such personal documents for research on the OT forced labour became apparent when, on January 15, 2019, Veerle Vanden Daelen received a message from Gaby Morris. Gaby wrote that her father along with a brother escaped Belgium in May 1940 to join the Czech army in exile and that they were evacuated to Britain. Both survived the war. Gaby’s father returned to Antwerp as a member of the liberating troops to discover that his parents and two younger siblings had been deported from the SS-Sammellager Mecheln (Dossin barracks) to Auschwitz-Birkenau, and were murdered. However, Kazerne Dossin then informed Gaby that in fact her grandfather, Meshulem, had been deported from Antwerp, Belgium, to the Organisation Todt labour camp Les Mazures in Northern France from where he was sent directly to Auschwitz. So it was her grandmother, uncle and aunt who had in fact been deported from Mechelen. This new information on OT labour led to many questions: What had been the consequences for the family left behind in Antwerp? What must the family’s situation have been like after Meshulem was taken away? Did they hear from him, directly or indirectly? Was there any support for these families in general?

So many unanswered questions with – in the case of Gaby Morris – nobody to testify about what happened. Could archival evidence then perhaps shed light on the situation of the OT families? Meetings with Gaby on International Holocaust Remembrance Day in 2019 and discussing with her the lack of knowledge on OT labour evolved into the Left Behind project. Kazerne Dossin and the Morris family joined forces to delve into this little known aspect of the racial persecution in Belgium, which had an especially large impact on Antwerp’s Jewish population: How did the OT campaign affect survival changes and how did the families deal with the absence of their men, fathers, brothers and sons? The goal of the project was to create an easily online accessible and understandable research product, which provides general information on the OT labour to a broad public. Kazerne Dossin was thus challenged to implement new research methods and presentation tools such as maps, which would turn out to be important research tools themselves in the course of the project.

Jewish Men From Antwerp in Forced Labour for Organisation Todt in Northern France

For the Left Behind project, it is important to understand firstly who was “left behind” and in which context. From June 13 until September 12, 1942, over 2.250 Jewish men from Belgium were summoned for forced labour in Northern France by OT. Six trains left from Antwerp, and one each from Brussels, Liège and Charleroi. The men were sent to the Les Mazures work camp in the French Ardennes or to similar camps at the French coast such as Dannes, Camiers, St-Omer or Calais. There they worked on constructions that would become part of the Atlantic Wall, such as roads, bunkers and electrical provisions. The large majority of these 2.250 men were from Antwerp. When they were taken away, they left behind their spouses, children, parents and further family and friends. During their detainment in France the men communicated with their loved ones and, in theory1, a very small wage was paid to their next of kin who had stayed behind in Belgium. Both elements could have prompted the families of these OT workers to remain at their legal address where the risk of being arrested was greater. In October 1942, most of the OT workers were directly deported from the labour camps in Northern France to Auschwitz-Birkenau, although dozens had escaped from the work camps already or would escape from the deportation trains. The Jews with Belgian nationality or those married to non-Jewish women were kept at the camps in Northern France in October 1942. They were deported later on from Drancy. Only a few dozen of the 2.250 men survived the war.

The obligatory labour of their men meant a huge transition for their families: from being part of the pre-war society to existing on the margins of it. However, the fate of these relatives remained unresearched. Existing historical publications focussed foremost on the OT-camps in northern France and the Jewish men taken there.2 No monograph or project was dedicated to the full picture of Jewish families in Antwerp with men sent to OT-camps in northern France. This project seeks to make those connections. It wishes to open up the already existing research to new audiences (by publishing in English, for example) and to broaden the scope of the research. In order to broaden and deepen the knowledge on the topic, we worked on a macro and a micro level. This included as a first focus the creation of a database to determine the deportation and survival percentages of the OT-men and their families. Parallel to this work, micro-histories were analysed on about 20 families, in order to seek for clues and pieces of information to reconstruct what happened to them. As a third element to the project, we wished to use maps for the public presentation of this history and the project. Soon it became apparent that the maps themselves were a third research element, a tool of analysis on their own. GIS or other geolocation tools could be used to add a time-element to such mappings to analyse and visualise the history. This blog contribution will further elaborate on each of these three focus points of the research project.

The creation of a database and datasets

When starting the project it seemed an easy task to establish a list of all Jewish men from Antwerp taken away to Northern France as slave labourers for Organisation Todt. After all, in 1978 the Belgian Ministry of Public Health had published the List of Jews living in Belgium on 10 May 1940, who were detained at the labour camps in the North of France. Conveniently, the list – containing data on the 2.252 recorded OT men from Belgium – had been put into an Access database by the Belgian Archives Service for War Victims. To kick off the data collection, we compared the list of 2.252 men with address records from 1940 to determine who lived in Antwerp at the beginning of the war. This allowed us to grapple how many victims living in the city at the time were affected by the OT labour and what their fate was. Within the data set, we could furthermore indicate how many of the men from Antwerp had left the city by the summer of 1942, before deportations from Belgium started in August 1942, and how many had remained in the port city until then.

So how to connect the list of 2.252 men with their 1940 address information? Kazerne Dossin has at its disposal the municipal Jewish registers which were created by Nazi decree of October 28, 1940. All address information from this rich source had already been connected with the deportation lists of the Dossin barracks in Mechelen in a Person Database. So for those of the 2.252 men that were deported from Mechelen, we could easily retrieve the address information and filter out the Antwerpians. For the men that were not deported from Mechelen, but from France or who were not deported the addresses were checked one by one to sort out the Antwerpians. This detailed research led to a list of 1.553 Jewish men, living in Antwerp in 1940 who were taken for slave labour in Northern France in the summer of 1942 (either from Antwerp or from Brussels, Liège and Charleroi). However, when consulting additional sources such as OT payroll lists, correspondence from the Association of Jews in Belgium, the list of men at the Les Mazures camp constructed by researcher Jean-Emile Andreux and personal testimonies it became clear that the list was incomplete. We therefore analysed these additional sources and added the newly found names to the deduced list of 1.553 men, leading to a final list of 1.625 Antwerpian OT men. We can therefore also conclude that the number of 2.252 OT workers taken from the whole of Belgium was, in fact, higher.

Subsequently, we divided the 1.625 men into 19 subpopulations based on their fate:

| Men who escaped from the OT camps and were not arrested again | 114 |

| Men released from the OT camps and not arrested again | 7 |

| Men escaped or released (unsure) from the OT camps and not arrested again | 24 |

| Men who died at the OT camps | 17 |

| Men deported from the OT camps to Auschwitz-Birkenau | 1097 |

| Men deported from the OT camps but who successfully escaped from the train | 34 |

| Men deported from the OT camps, who escaped from the train and who were deported again | 27 |

| Men deported from the OT camps, who escaped from the train, who were deported again and successfully escaped the train | 3 |

| Men deported from the Dossin barracks to Auschwitz-Birkenau | 181 |

| Men deported from the Dossin barracks but who successfully escaped from the train | 6 |

| Men who died at the Dossin barracks | 2 |

| Men released from the Dossin barracks | 14 |

| Men liberated at the Dossin barracks in September 1944 | 8 |

| Men deported from the Drancy camp to Auschwitz-Birkenau | 28 |

| Men deported from other camps to camps in the Reich | 12 |

| Men released from other camps in France and Belgium | 3 |

| Men who died at other camps in France and Belgium | 13 |

| Men liberated at other camps in Belgium in September 1944 | 5 |

| Men liberated in France in September 1944 | 30 |

Table: An overview of the 19 subpopulations and the size of each

These categories will later on allow us to compare the fates of the families of the men between groups, so as to establish whether the actions of the man had an impact on the fate of his family. E.g. Did relatives of men who successfully escaped the OT camps have higher chances of survival than the families of the men that were deported directly from the OT camps to Auschwitz-Birkenau? As it was not possible, time wise, to research the families of all 1.625 Antwerpian OT workers, we created a research sample. This included all men from the 17 smallest categories, and a relevant percentage of the men in the two largest categories. For all further calculations a weighted average was used to sort out the weight of the two largest categories in comparison to the smaller ones. In total, 628 of the Antwerpian men were included in the research sample.

In a next step, we added address information from the summer of 1942 to the data of the men in the sample to be able to determine who had left Antwerp by the time they were claimed by Organisation Todt and where they moved to, on which date. This data can illustrate the social movement away from Antwerp and the precautions taken by some of the families to avoid the forced labour by leaving the city. Based on an extrapolation of the research sample we can state that an estimated 1.528 of the 1.625 Antwerpians were still in Antwerp when taken for Organisation Todt, which is in line with the numbers of 1.518 and 1.526 men taken from Antwerp as mentioned in official OT sources.

The last, and largest step in the project was to identify the relatives of the 628 men from the research sample. Using records such as the municipal Jewish registers, a list was created containing 1.501 family members of the OT men from the research sample. Family members were defined for the project as next of kin living at the same address in Antwerp as the OT worker. For each of these relatives information regarding his or her fate was collected, as well as data on the way in which a person was arrested (if applicable) and if he or she survived deportation. Based on this analysis, we can now explore the timing of deportation of the slave labourers as well as the timing of the arrest of their family members who remained at home. Also, the deportation numbers of OT relatives can now be compared to the deportation rates for Jews in Belgium and more specifically in Antwerp. Forthcoming publications will elaborate on the specific numbers and place them in context.

The importance of microstories

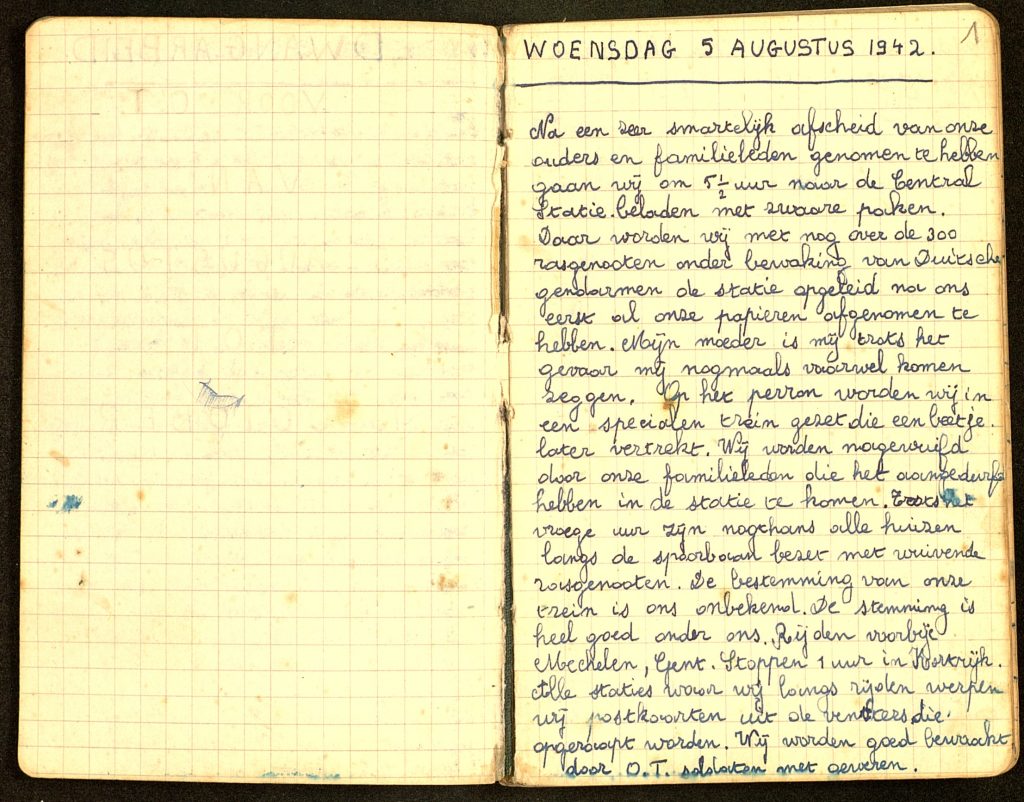

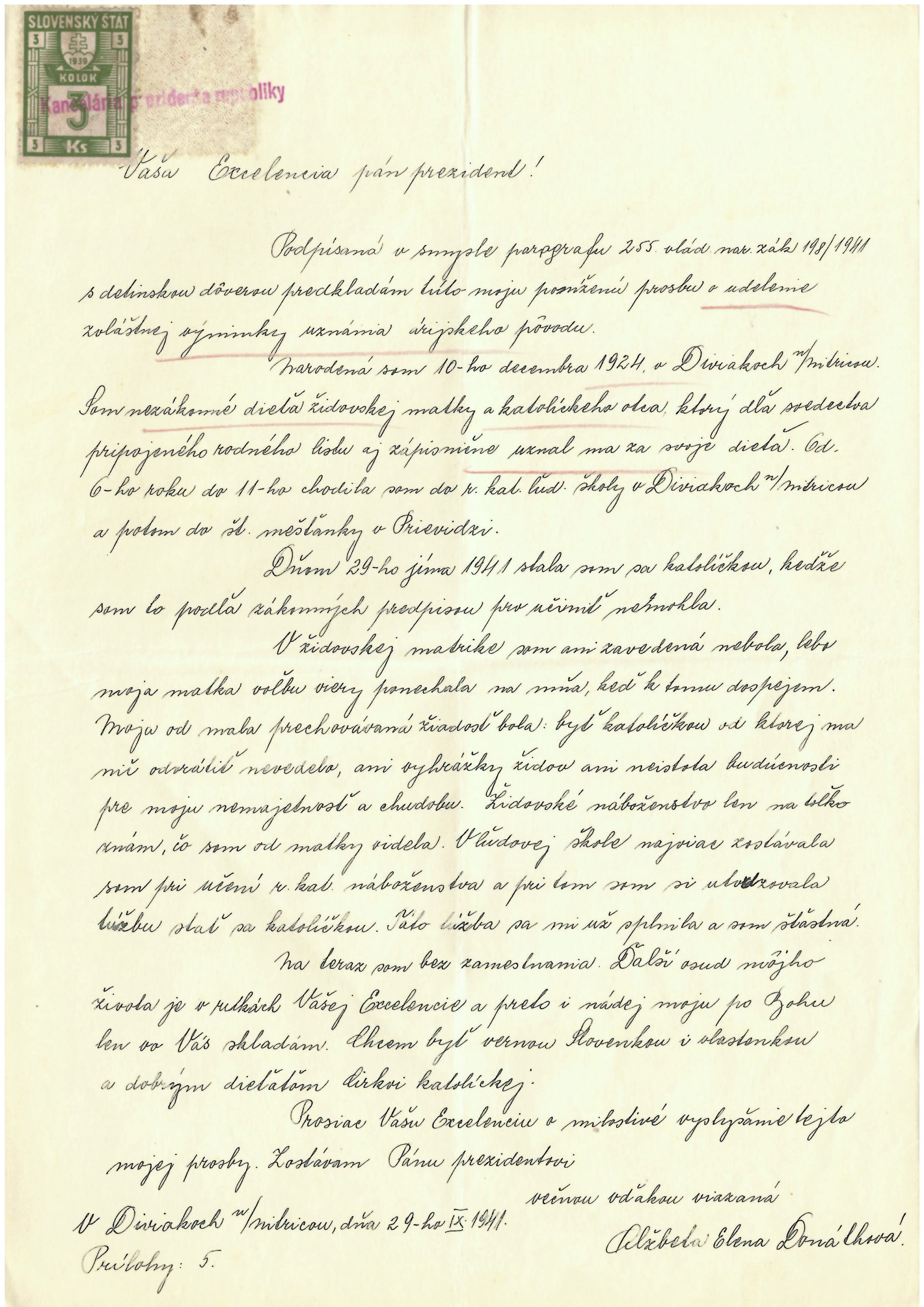

Apart from delivering statistical analysis, the Left Behind project seeks to translate macro history, based on the above mentioned data, into micro history, based on personal stories and items, and vice versa. Both elements of research enhance each other and lead to new insights into the lives and fates of Holocaust survivors and victims. For the Left Behind project, on a micro-historical level, Kazerne Dossin has documented personal stories of about 20 Antwerpians to illustrate communication lines between the OT workers and their families. By using documents such as the diary of Mozes Sand, personal letters, photographs and testimonies of relatives of OT workers, relevant data is collected. Furthermore, we try to connect the macro analysis of the deportation and survival rates with these microhistories. Can elements from these microhistories help explain the deportation and survival rates?

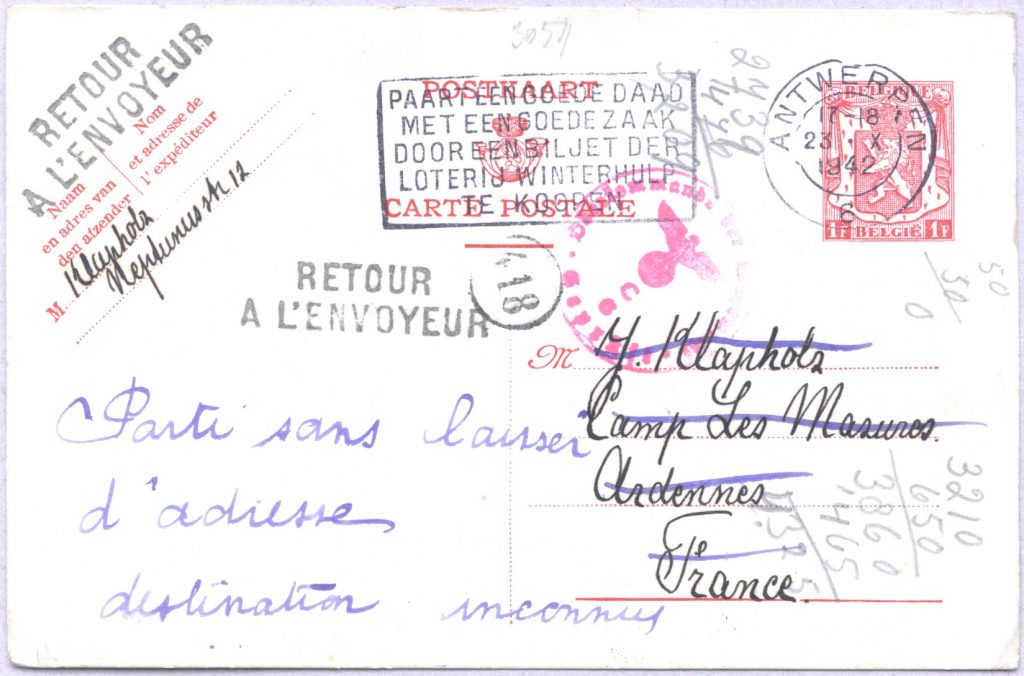

Although not expected when starting the research project, it soon became apparent that multiple ways of communication existed between the OT men and their families. These are described in detail in sources such as the diary of Mozes Sand. An in depth study of the document led to the identification of several official and unofficial communication channels, including the shipment of parcels and letters either via censored mail or clandestinely posted by non-Jewish coworkers met at the construction sites, visits to the families in Antwerp by non-Jewish coworkers, the arrival of news via new transports of workers from Antwerp and even (clandestine) visits to the men in the OT camps by their relatives. Most OT workers as well as their families have been deported and wiped out, making it impossible to determine if communication existed and if so, how it influenced the decisions made by the OT men or their families. The remaining traces of these communication lines are therefore of the utmost importance. A series of postcards exchanged between Mathilde Kornitzer, living in Antwerp, and her husband Jacob Klapholz, an OT worker held at the Les Mazures camp, show how they maintained contact after Jacob was taken. The last postcards Mathilde sent him mid-October 1942, were returned to her, indicating that Jacob had left, “destination unknown”. He had been deported and would not survive Auschwitz-Birkenau. Mathilde correctly interpreted the signs and went into hiding. She thus survived.

Vice versa, the establishment of contact between the families in Antwerp and the workers in the North of France could create dangerous situations for the women and children left behind in the port city. This is illustrated by the story of Anna Erlich. Both her father Szymon Erlich and her cousin Vital (called Bertrand) Liebermann, were OT workers. Anna, her sister Rosa and their mother remained at their official address. Photos sent by Bertrand to his cousins and aunt in Antwerp show that communication was still ongoing in 1943. The three women were arrested in autumn that year and only Anna survived. Receiving and sending messages thus could also lead to greater danger and the arrest of entire families.

Many letters, postcards and photos exchanged between the OT men and their families are lost. And for many families there might not have been any communication at all since Antwerp was hit by four large raids in August and September 1942, leading to the deportation of hundreds of relatives of the OT men, before their own mass deportation in October 1942. However, such micro studies do allow us to illustrate some of the possible reactions to the existence of such communication and to take into account the impact of news on both the men and their families.

Mapping: from public outreach to research tool

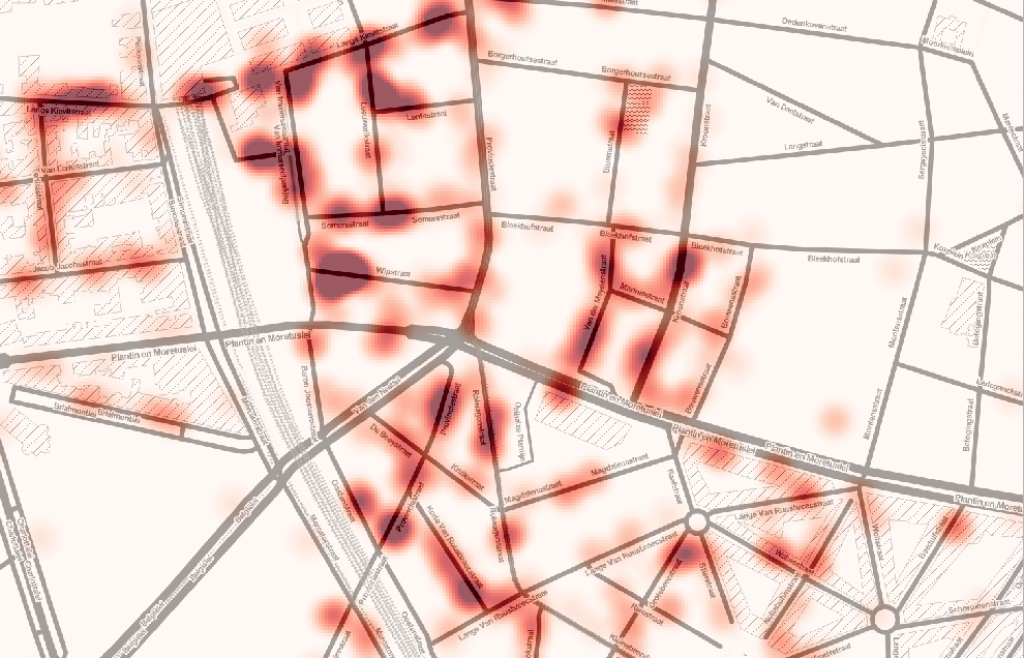

Combining micro and macro analysis for both an academic and a wider audience has always been a core element in the Left Behind project. The visual part was initially only included as a tool for academic presentations and publications, and to invite a broad audience to engage with both the statistical research and the personal stories. We envisioned the results of both approaches to be included in academic publications and in a product for a wider audience such as a – commemorative and/or educational – website or app. Although we initially thought of mapping as an ‘easy access’, the data gathered on the families’ movements and timing of their arrest also led to additional research questions, incorporating the mapping element as a third important research step for the Left Behind project. The visualisation of the data on both the complete population of OT families as well as on individual workers and their families, created an extra value/layer in the analysis as the maps also allowed us to pose additional research questions: e.g. Did OT relatives live in the same areas as the other Jews in Antwerp or is there a geographical distinction? And were the relatives deported earlier or later than non-relatives?

As a small institute, however, Kazerne Dossin was faced with very limited experiences with mapping, and especially visualising stories via maps. Wolfgang Schellenbacher (DÖW) was so kind as to guide us through the possible outcomes and to create maps for the project. Kazerne Dossin delivered an overview of the addresses of the families, which he transformed into geo-coordinates. Via trial and error we learned how to ‘clean up’ the addresses included in the datasets. A few streets mentioned in the 1940 registers do not exist anymore today and need to be set out approximately where the streets used to be, and in some cases, the numbering of the houses in some of the streets may have changed, leading to less precise indications of the exact houses for a small amount of data in the historical dataset. Three heat maps were created via QGIS, a free and open-source cross-platform, which gave a visual overview of the dispersion of the OT families in Antwerp and especially the concentration of these families, mostly within the Jewish neighbourhood of Antwerp. The three maps all focused on the city, but from a different height, thus showing more details or less, depending on the area that was shown on each map.

In addition to the dispersion of the families at one point in time, we also wished to show the public – both academic and general – how certain events impacted the OT families. Many fell victim to the four large raids in Antwerp in the summer and autumn of 1942. Adding a timeline to a map of Antwerp allows to combine geo-spatial and time elements, e.g. who was arrested during the first large raid in Antwerp, who during the second, who received a convocation for forced labour, etc. We considered multiple licenced software packages, but all came with quite high licence fees and the necessity to have experience with GIS or even programming, or they did not allow us to combine time and space data. Neatline software was used to create more detailed and interactive maps of Antwerp, based on the geo-coordinates already provided. These maps also included a time element which allows users to switch between certain moments in time.

See fullscreen visualisation of “OT families and the raids in Antwerp”:

Mapping the addresses of the OT families and the raids in Antwerp was made possible by Neatline (an Omeka plugin).

In the future, to fully present the research data to a wider audience and to continue to analyse geospatial data by using maps, we wish to include the information on the members of the families in the map, mentioning their names and dates of birth when clicking on a certain address (but of course in compliance with the GDPR for those that survived). Neatline does not provide a function to upload both the address and the person data in one sequence: one can upload the address data but then has to put in manually the person data. Doing this for 1.501 persons would be too time consuming. Kazerne Dossin has therefore partnered up with the city of Antwerp to use the licensed ArcGIS software. This will allow us to incorporate time, space and personal data in the overview map, but will also allow us to create maps showing the personal journey of some of the families. However, for institutes that want to analyse and show large datasets, Neatline remains highly recommended.

Conclusion

This project started with Ms. Gaby Morris searching for answers on the fate of her family, deported from Belgium during the Holocaust. This endeavor led her to Kazerne Dossin as her family members were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau from the SS-Sammellager Mecheln in 1942. Microhistorical research further revealed the obligatory slave labour in Organisation Todt labour camps in Northern France to which Ms. Morris’s grandfather had been forced, together with over 2.250 Jewish men from Belgium, including 1.624 fellow-Antwerpians. Without any direct documents from the family itself, it became clear that Ms. Morris’ grandmother was left behind in Antwerp with the youngest children in a most vulnerable situation. Hundreds of other Jewish families from Antwerp found themselves in the same position and little was known about their fate. With the Left Behind project Kazerne Dossin’s research team aims to advance knowledge on this little known aspect of Holocaust history in Belgium and seeks to explore the combination of micro, macro and spatial analysis, incorporating personal stories, analysis of large datasets and analysis of time and space elements on interactive maps into one research project. As such, Left Behind wishes to visualize its findings for both academics and a wide audience. At the same time, the team expects the mapping of data related to time and location to also have an increasing impact on and contribute to in depth academic analysis. The first research results indicate that the OT slave labour of Jewish men from Antwerp and the impact it had on their own as well as their families’ fate may well be an important factor in explaining the higher deportation number in Antwerp as compared to other large cities in Belgium and the country’s general deportation rate.

- The archives of the Association of Jews in Belgium (Jewish Council) demonstrate that wages have been paid. However, it remains unclear who received what and it is certain that not all families received wages. In any case were the wages for Jewish obligatory labour much lower than for a non-Jewish (voluntary) worker. ↩

- Andreux, Jean-Émile. “Les Mazures, un camp de juifs en Ardennes françaises.” Tsafon: Revue d’études juives du Nord 46 (2003-2004): 117-147; Andreux, Jean-Émile. “Mémorial des déportés du Judenlager des Mazures.” Tsafon: Revue d’études juives du Nord 3 hors-série (2007): 35-121; De bezittingen van de slachtoffers van de jodenvervolging in België. Spoliatie – Rechtsherstel. Bevindingen van de Studiecommissie. Eindverslag van de Studiecommissie betreffende het lot van de bezittingen van de leden van de joodse gemeenschap van België, geplunderd of achtergelaten tijdens de oorlog 1940-1945. Brussels: Diensten van de Eerste Minister, 2001; Delmaire, Danielle. “Les camps des Juifs dans le Nord de la France (1942-1944).” Memor. Bulletin d’information 8 (1987): 47-65; Delmaire, Danielle. “Table ronde. Les ‘camps de juifs’ dans le Boulonnais (1942-1944). Actes de la table ronde de Boulogne-sur-Mer, 24 septembre 1988”, Memor. Bulletin d’information 10(1) (1989): 9-31; Desquesnes, Rémy. “L’Organisation Todt en France (1940-1944).” Histoire, économie et société 11-3 (1992), 535-550; Gaida, Peter. “Les camps de travail de l’Organisation Todt en France, 1940-1944.” Les Cahiers de la MSH Ledoux 10 (2007): 235-256; Godfroid, Anne. “A qui profite l’exploitation des travailleurs forcés juifs de Belgique dans le Nord de la France.” Bijdragen tot de Eigentijdse Geschiedenis 10 (2002): 107-127; Rigaut, Rudy. “Les particularités de la zone côtière dans la persécution des Juifs dans le Nord et le Pas-de-Calais occupés (1940-1944).” Tsafon: Revue d’études juives du Nord 79 (2020): 39-74; Schram, Laurence. Dossin: Wachtkamer van Auschwitz. Tielt: Lannoo, 2018.; Steinberg, Maxime. L’étoile et le fusil. La question juive 1940-1942. Brussels: Vie Ouvrière, 1983; Steinberg, Maxime. L’étoile et le fusil. 1942. Les cent jours de la déportation des Juifs de Belgique. Brussels: Vie Ouvrière, 1984; Vandepontseele, Sophie. “De verplichte tewerkstelling van joden in België en Noord-Frankrijk.” In De curatoren van het getto. De Vereniging van de joden in België tijdens de nazi-bezetting, edited by Rudi Van Doorslaer and Jean-Philippe Schreiber, 149-181. Tielt: Lannoo, 2004;Van Doorslaer, Rudi, ed. Gewillig België. Overheid en Jodenvervolging in België tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog. Antwerpen and Amsterdam: De bezige bij, 2007. ↩

One Comment Leave a reply